“Earlier, we used to say, take your time and have a baby. But now the situation has changed… Now I would not say don’t hurry.” That’s not just any ordinary neighbourhood uncle being pushy about your reproductive choices. That’s MK Stalin, chief minister of Tamil Nadu, speaking to newlyweds – he was literally at a wedding – who hail from the state.

“There is a situation that only if we have a large population, we can have more MPs. This situation has emerged because we succeeded in effective population control. Get children immediately, but give them beautiful Tamil names.”

Why is Stalin asking the people of Tamil Nadu to have children immediately?

The answer is ‘delimitation’, a topic I’ve written about at length on this newsletter and elsewhere. (See: Why India’s new Parliament building may spark a North-South tug-of-war and Will the states vs Centre battle dominate India over the next decade?), as well as these pieces:

Why South Indian states are up in arms against Modi and the BJP

The argument, or at least that bit of it that prompted the ‘my tax, my right’ protests, is summarised by this oft-used line: “When we pay Rs 1 to [the Government of India], the union government devolves only 29 paise. But Uttar Pradesh, where BJP is in power, gets Rs 2.73 in return for a contribution of Rs 1.” In other words, the industrious South makes all the money, only to see it taken away by the Union Government and plowed into the North for political gains.

Ageing South India and a census-delimitation 'trial balloon'

The idea of an ageing South India has a number of implications – cultural (not least in the large number of North Indian workers moving South), societal (is Indian society prepared to deal with a larger elderly population?), governmental (can healthcare systems keep up?) – and federal.

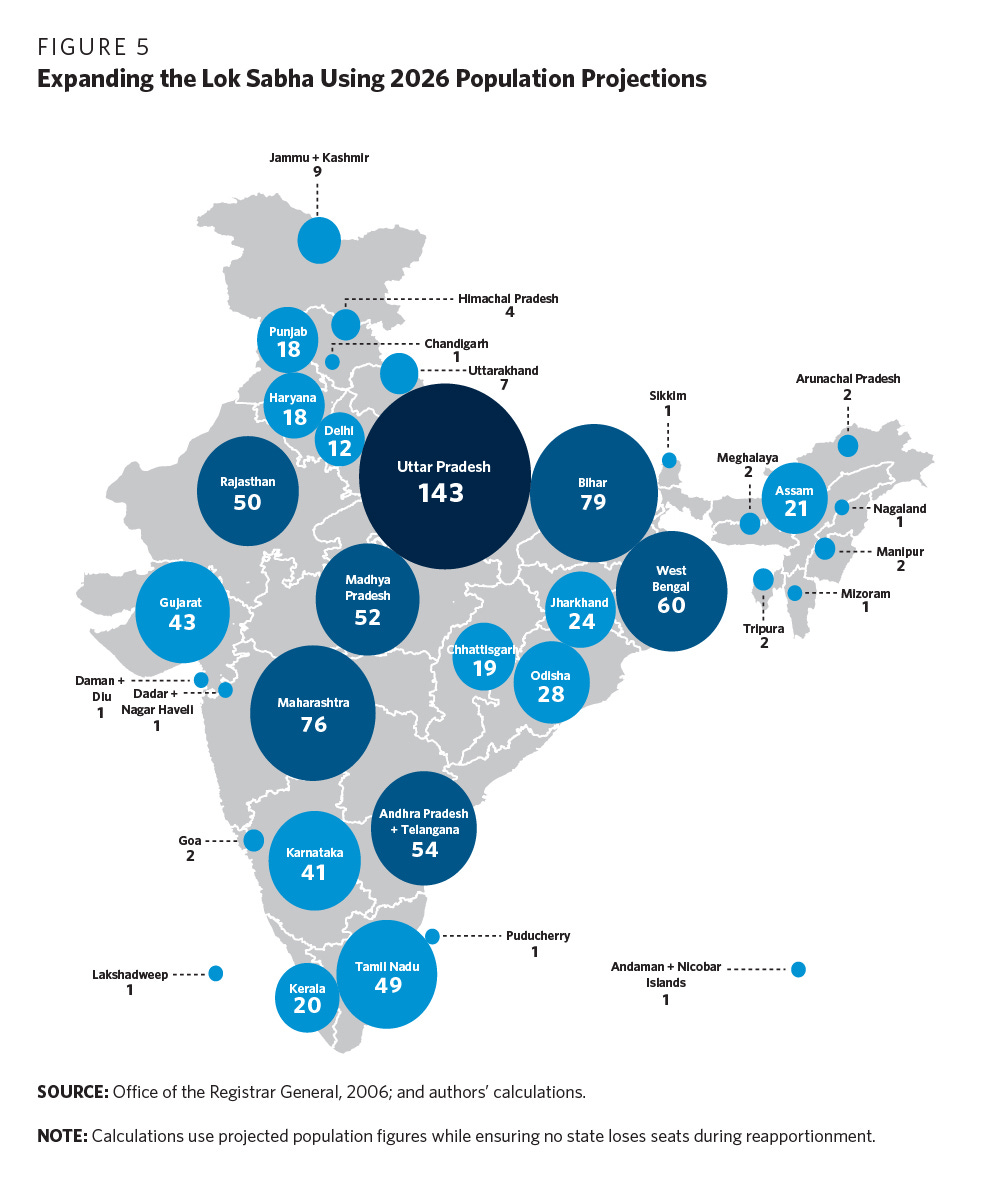

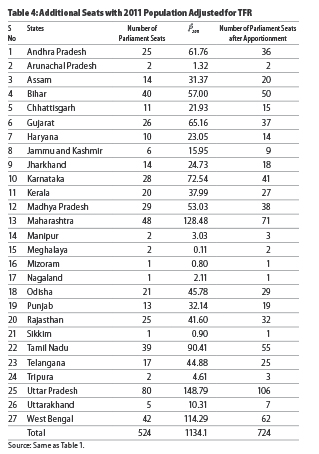

Quick recap: The distribution of seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian Parliament, was supposed to be updated every decade to reflect changes in population. But, for a number of reasons, the process of re-adjusting seats has been frozen since the 1970s. This has meant a huge disparity in the sizes of constituencies in the (higher fertility) North versus the (ageing, low-fertility) South and, as a consequence, an undermining of the principle that each person’s vote is equally valuable. This ‘malapportionment’ is supposed to end after 2026 in a process referred to as delimitation. Were it to be carried out based on updated population figures though, it would result in a huge change to the balance of power in Parliament. Either South Indian states would lose a number of their seats, or, as indicated by the new Parliament building, the Lok Sabha will be expanded in a process that, per some calculations, would give Uttar Pradesh alone as many seats as all the South Indian states combined. Leaders of southern states have described this as a ‘damocles sword’ having over the region.

At a time when he has also been squabbling with the Union government over the three-language policy and allegations of Hindi imposition, Stalin called an all-party meeting (of parties registered in Tamil Nadu) on March 5 to discuss delimitation, with the aim of drafting a ‘joint response.’ The Bharatiya Janata Party and its ally, the Tamil Maanila Congress, have both decided not to go.

Meanwhile, Home Minister Amit Shah insisted that “southern states will get a fair share, there is no reason to doubt this.” Shah’s statement is unlikely to assuage anyone in the South because neither his government nor party has offered any details regarding how they are approaching the delimitation issue, outside of broad platitudes.

The party’s only firm claim has been that the South will not lose any seats. The BJP’s state president, for example, referenced a speech by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2023, in which he argued that, if the Congress’ campaign logic on caste-based reservations were instead applied to the delimitation question, “South India stands to lose 100 Lok Sabha seats” – implying that this was not what the BJP would do. Shah, speaking last week, insisted that “the Modi government has made it clear in Lok Sabha that after delimitation, on pro rata basis, not a single seat will be reduced in any southern state.”

But not losing seats would make little difference to the concerns raised by the Southern states, if the increase were based purely on population projections, as Alistair Macmillan suggested nearly 25 years ago, depicted in this visualisation by Milan Vaishnav and Jamie Hintson’s important 2019 paper on this issue.

Leaders of southern states have also struggled to articulate a way forward.

They could of course just ask for the can to be kicked down the road again, as it was in 1976 and then in 2002 (when a BJP-led coalition was at the helm). Those delimitation freezes were expressly predicated on the idea that states should not be punished politically for successful family planning, which was official policy1. Perhaps at some point in the future – though Stalin’s urging is unlikely to be a sufficient cause – population figures may converge, and then delimitation would matter less.

(One analysis even suggests that increased internal migration to South Indian states will, over time, moderate the population loss they face because of lowered fertility rates – though this argument is predicated on the idea that migrants will be, or ought to be, counted as residents, and ignores the already significant gap that has emerged between the regions over the last half century since delimitation was last conducted).

This argument might build on the population control framing, but also relies on the idea that ‘one person, one vote, one value’ – the principle on which constituencies are expected to have similar sizes – has always been a somewhat flexible concept, amenable to adaptation in case where other political equity questions are at stake. (For example, sparse-population states in other democracies are sometimes granted seats beyond what they would be due to ensure representation). It also derives support from the conclusion that India’s ‘malapportionment’ problem is not unique globally nor, according to one study, even particularly egregious.

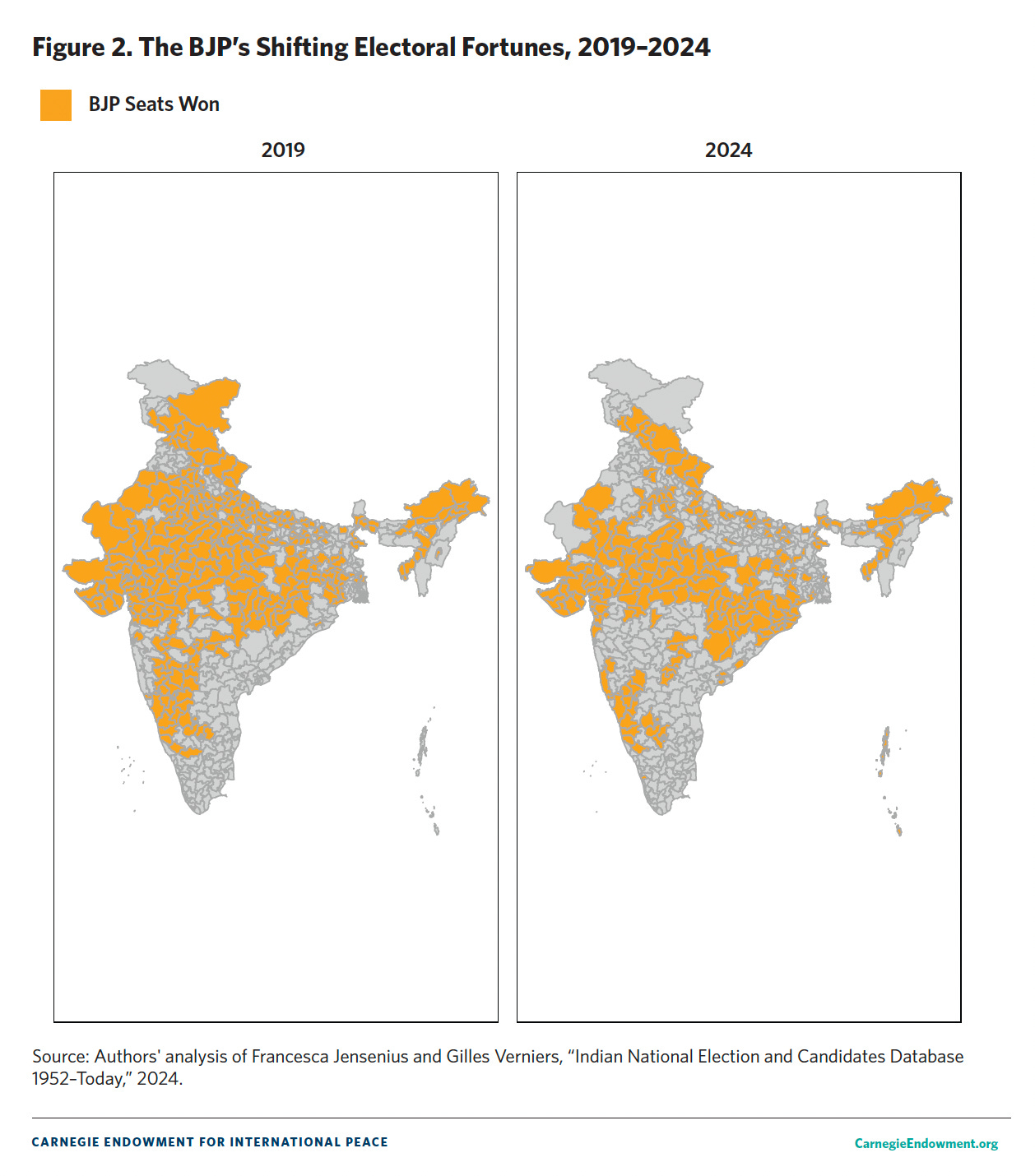

The legislative challenge for votaries of postponement, however, is simply that delimitation is the default scenario: As per the Constitution, it has to be conducted based on the first census after 2026. Note also that the census originally scheduled for 2021 has yet to be carried out for a number of reasons, as I wrote here, and may well now take place just in time to fulfill this criteria. Moreover, the interests of the ruling BJP dovetail well with actually conducting the delimitation exercise, given that, despite the losses it faced in the 2024 elections, its core support still comes from the North.

(Of course, if bulldozed through, delimitation may significantly threaten India’s federal compact, but Modi has, time and again, demonstrated a preference for shock-and-awe tactics over consultative ones, and a willingness to unsettle the status quo, as with the writing down of Article 370 and the Citizenship Act amendments).

This means the South would have to mobilise support to stop or alter delimitation through another constitutional amendment2, a difficult task given numbers in Parliament. Moreover, the default option is not just delimitation, but reapportioning of seats based on the current Lok Sabha strength, which effectively means the South losing seats. If Southern leaders wanted to at least guarantee that they do not lose seats – an outcome that has many ramifications for the pathways to power within a state – they are incentivised to collaborate with the BJP towards a constitutional amendment that enables a bigger Parliament.

The latter opens up the space for a compromise or alternative proposals, but what could those look like?

A few different options have been put forward. Bharath Rashtra Samithi’s KT Rama Rao has called for delimitation “based on fiscal contributions to the nation.” Others have argued for a grand federal bargain (as pitched here by

and Suman Joshi), involvingan increased devolution of expenditure funds from the Union to the states,

a revision of the lists that divide policy concerns between the Union and states, restricting the former only to subjects of national importance,

reducing centrally sponsored schemes, which are seen as limiting the agency of states to spend as they see fit,

and, most significantly, transforming the Rajya Sabha, India’s upper house, into a Senate-style body where each state has equal representation (as opposed to the current system, where the Rajya Sabha’s seat distribution simply mirrors the Lok Sabha, relying on the same population figures, and where representatives don’t even have to be domiciled in the state they represent).

Do any of those seem likely?

The Modi government did indeed manage to institute a grand federal bargain back in its first term, the Goods and Services Tax, but the conditions for one today seem much less propitious. Aside from the change in personnel – Arun Jaitley is no longer around – the BJP has also spent the last decade undermining any trust it might have had across the aisle, as a consequence of its brazen efforts to stymie the functioning of Opposition-led states, using everything from investigative agencies to the nominally apolitical office of the governor.

History suggests the BJP will set out to use the bare minimum of carrots (in the GST case, for example, it relied on a compensation cess that acted as only a temporary salve) and heavier sticks to get to its objectives. The much touted Women’s Reservation Bill, which would set aside 1/3rd of seats in Parliament for female candidates, was made contingent on delimitation – generally interpreted as a tactical move to blunt opposition to reapportionment of Lok Sabha seats.

Outside of its greater reliance on the TDP in the current parliament, there is one factor that might seek to curb the BJP’s potential excesses on this front: Its own aspirations in South India. The party has long sought to become a larger player in each of the Southern states. It has already held power in Karnataka, where it is now in Opposition, and has made major gains in the other states over the last decade, if only in terms of vote share. An approach that is unmindful of Southern concerns would threaten this, with even RSS-linked outlets cautioning against such actions.

Still, the fact that the BJP has chosen platitudes – “there will be no injustice to the Southern states” – over a consultative process suggests that it either has not settled on a final formula or is waiting for an opportune time to make a rapid legislative push. What is clear is that the DMK, which faces elections in Tamil Nadu in 2026, and other Southern parties are not willing to simply wait until delimitation is a fait accompli.

Read also

This paper by Lalit Panda and Ritwika Sharma that carefully examines a number of the assumptions and logics in play when considering delimitation, and offers a few more options (‘degressive proportionality’) to address the various concerns.

Research by Rikhil Bhavnani showing how malapportionment has impacts on cabinet inclusion and economic development, and another study by Ursula Daxecker that even claims an impact on election violence.

My interview last year with Louise Tillin, on how Indian Federalism has evolved under the BJP.

”Keeping in view the progress of family planning programmes in different parts of the country, the government, as part of the national population policy strategy, recently decided to extend the current freeze on undertaking fresh delimitation up to the year 2026 as a motivational measure to enable the state governments to pursue the agenda for population stabilisation.”

The caveat here is that just because something is law doesn’t mean it is automatically executed, as protests against the land law amendments back in 2014, as well as the farm laws in 2021 demonstrate.

If only we discussed with equal interest why cities in Maharashtra, Karnataka, and other states have not held elections, solved ward delimitation issues, and are experiencing a complete governance breakdown. The complaints about roads, pollution control, informal markets, and waste management we see daily in the news and social media could be symptoms of a more significant systemic failure. India and China began decentralisation in the 1980s with the Panchayati Raj or whatever they call it across the Himalayas, but look at the stark difference today. Corruption is common on both sides. We are democratic on paper at the grassroots level, but only if the system can function.

Why is delimitation bad? Southern states deserve more vote share with less people? So their votes matter more?