Why South Indian states are up in arms against Modi and the BJP

The 'My Tax, My Right' campaign, delimitation and more.

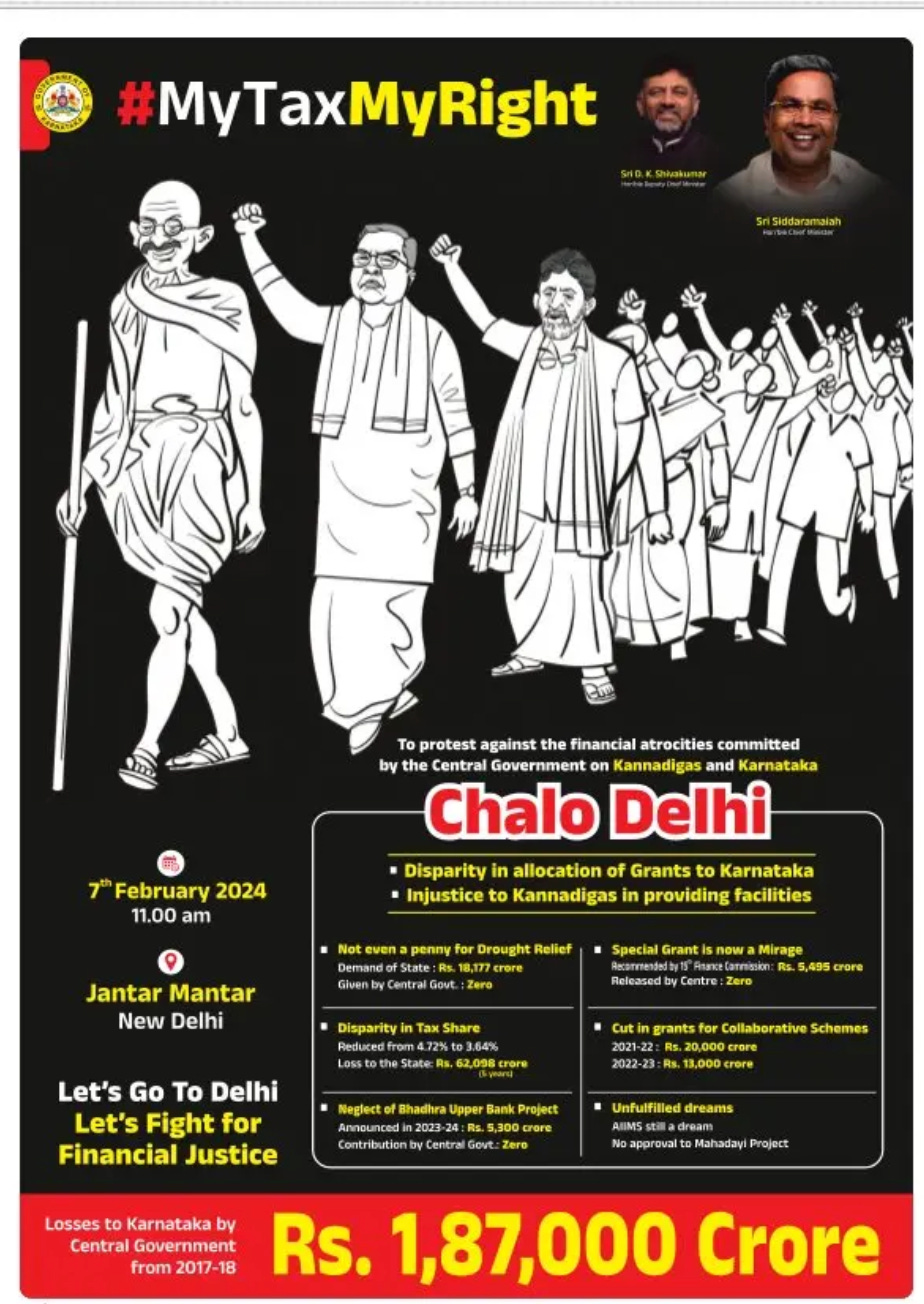

Full-page newspaper advertisements for politicians, parties or governments are an extremely common phenomenon in India. And the figure of ‘Mahatma’ Mohandas Gandhi turning up in these ads is not unusual either. Yet, despite that context, the visual that turned up across newspapers on February 7 was a break from the norm:

Instead of election promises, the announcement of new projects or claims about government achievements, the ad featured Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah and Deputy CM DK Shivakumar, of the Congress, at the front of a protest march of faceless citizens, preceded only by a (bemused? smirking?) Gandhi. The demand? Justice for ‘financial atrocities’ committed by the Union Government on Karnataka. The campaign was accompanied by a sit-in in New Delhi, and supported by leaders of other states, including Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

The effort evidently struck a chord.

“Today I want to share my pain on a specific matter,” said Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Parliament that week. “The way language is being spoken these days to break the country, these new narratives are being made for political gains. An entire state is speaking this language, nothing can be worse for the country than this... what language have we started saying… 'Hamara tax hamara money', (Our tax, our money) what is this language being spoken? Stop giving such new narratives to break the nation. It poses a threat to the future of the country.”

Why are South Indian states demanding their ‘fair share’ of tax collections in India?

More on this below, but first a couple of plugs.

This week, on the Election Tricycle (which I co-host with Emily Tamkin and Tom Hamilton), we spoke about electoral bonds and money in elections in India, the US and UK, and whether you can spend your way to victory. Subscribe to the show on Apple, Spotify, or elsewhere, and send feedback, suggestions or funny election stories for us to flag.

Also, on BBC’s The Briefing Room, hosted by David Aaronovitch, I spoke about the state of Indian democracy ahead of this year’s general elections. Listen here.

Finally, as I mentioned last week, I’m going to be in Philadelphia (as a Visiting Fellow at the Center for the Advanced Study of India, University of Pennsylvania, where I also help edit and commission for India in Transition) over the months of April and May , with plans to visit New York and Washington, DC to meet scholars, analysts and anyone else working on India. If you’ll be around at the time, and might be interested in meeting, please do get in touch – either by replying to this email or writing to rohanvenkat AT gmail.com

Vindhyan variance

The broader issue at hand is often reduced to a simple (and simplistic) formula:

North India vs South India.

In this reading, ‘North’ is used as a short-hand for populous, poor, Hindi-speaking states that feature sputtering economies, miserable human development indicators and immense support for the BJP and Modi. In contrast, ‘South’ refers to economically developed, socially progressive non-Hindi-speaking states where the BJP’s Hindutva agenda has struggled to take root.1

The argument, or at least that bit of it that prompted the ‘my tax, my right’ protests, is summarised by this oft-used line by Tamil Nadu Minister Thangam Thannarasu: “When we pay Rs 1 to [the Government of India], the union government devolves only 29 paise. But Uttar Pradesh, where BJP is in power, gets Rs 2.73 in return for a contribution of Rs 1.”

In other words, the industrious South makes all the money, only to see it taken away by the Union Government and plowed into the North for political gain.

How accurate is this story?

First let’s break down some of the factors that drive this current North-South divide discourse.

Socio-economic disparity

That there is a huge gap between the South (referring to the states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Telangana and Andhra) and the North (most clearly represented by the large states of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Bihar2) on economic as well as human development indicators is evident.

As Nilakantan S put it in a piece for the BBC in 2022:

“A median child born in southern India will live a healthier, wealthier, more secure and a more socially impactful life compared with a child born in northern India.

In many of these indicators of health, education and economic opportunities, the difference between the south and the north is as stark as that between Europe and sub-Saharan Africa.”

Why is that? And has it always been the case?

The answer to this is a bit more complex. In The Paradox of India’s North–South Divide: Lessons from the States and Regions (2015) Samuel Paul and Kala Seetharam Sridhar took a shot at the question and concluded that the economic divide was a “relatively recent phenomenon”, with data suggesting that the Southern states only began surging ahead in the late 1980s. Since then the two regions went from relatively even to so far apart that the South’s per capita income was more than double that of the North by 2005.

The book posits a number of potential explanations for why this might have happened – political stability, progressive policies, resource efficiency, investment in human capital. If you put aside the question of why and how, the ‘so what’ is still important: This is a case of a large (and, on many indices though not all, growing) socio-economic divergence within a country, which means political disputes and debates about the disparity are inevitable.

The flip side of this economic success has, however, meant that the share of taxation funds passed on to these states has been falling over the past few decades, since the Finance Commission – which calculates this split – prioritises moving funds to poorer and more populous states, with less consideration given to resource efficiency or ‘success’ of population control measures.

BJP hegemony

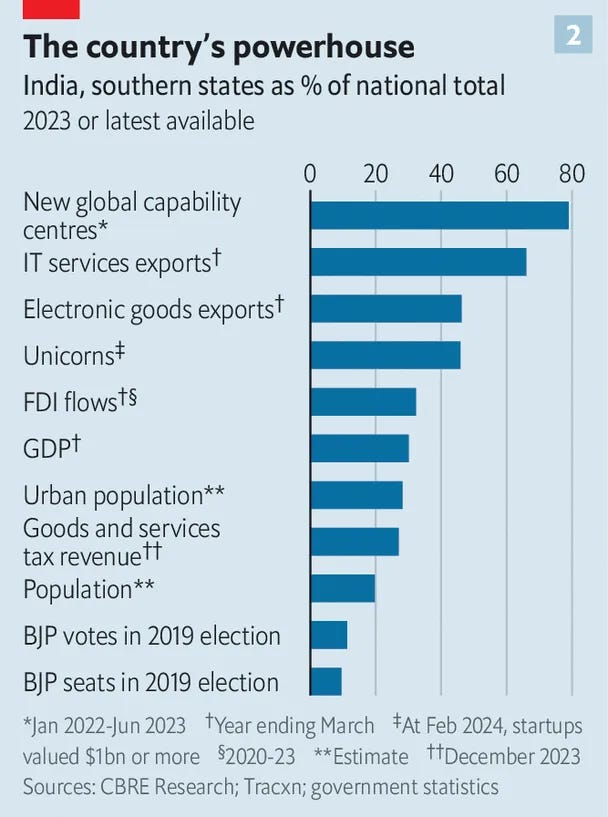

Now place that against the growing political hegemony of the BJP. It has been argued that India has entered a “fourth party system”3, one where Modi’s party is dominant and indeed represents the pole around which politics in the country arranges itself. An important aspect of this hegemony – which seems entrenched at the national level but is shakier at the level of states – is that it is heavily tilted towards the North.

Today’s BJP is much more pan-Indian than its 1980s avatar and it has made concerted efforts to broaden its appeal and second-rung leadership well beyond the ‘Hindi heartland’. But there is no doubt that its core support base, as well as the thrust of its politics, lies in in the North.

As we have discussed before, the Opposition has struggled to come up with a national narrative to take on the BJP’s potent mix of Hindutva, development and welfarism. Instead, the most successful opposition to the party has come from parties that are able to mobilise regional pride and depict the BJP as a party of Hindi-speaking outsiders that seek to impose their language and culture on the rest of the country.

Centralisation under Modi

Despite his earlier avatar as a chief minister who railed against the dictatorial tendencies of the Union Government in Delhi, Narendra Modi’s tenure as prime minister has been marked by significant efforts to centralise both governance and politics.

Modi’s administration is most commonly identified by various centralising ‘One Nation’ policies, brazen use of technical tweaks (cesses and surcharges) to avoid having to pass on tax revenues to states, and the unabashed weaponising of centrally appointed governors against state administrations run by Opposition parties. The BJP’s own politics has been heavily built around the prime minister himself, depicting welfare programmes (which are generally implemented by state governments, and only partially funded by the Union) as a gift to voters from the nation’s leader.

These centralising tendencies have led to deep suspicions about the Union Government’s intentions and impartiality in any situation involving federalism.

As R Ramakumar has argued, never mind how it is distributing funds between states, there are fundamental questions about whether the Union Government has been unfairly holding onto money that ought to belong to (all of) the states.

Delimitation 'Damocles sword’

I wrote about this at length a few years ago, and also made mention of it in a piece suggesting the Centre vs States battle may be one of the major faultlines in Indian politics over the 2020s.

Briefly put: India’s Parliament has frozen the number of seats it has since the 1970s, despite massive changes to the country’s population since then. The freeze was put in place in part because population control was official government policy at the time, and so ‘rewarding’ North Indian states with more seats for their much higher fertility would have been politically problematic. That can continued to be kicked down the road every 10 years, until we got to a point where the disparity is massive. One Member of Parliament from Tamil Nadu now represents on average 1.8 million citizens, whereas an MP from Uttar Pradesh represents 3 million.

Ever since Modi inaugurated India’s new Parliament (which has space for 888 Lok Sabha MPs, as opposed to the current 543), there have been indications that he would seek to unfreeze the issue when it comes up next in 2026. And why wouldn’t he? Projections suggest that the reconstituted Lok Sabha would feature a whopping 143 seats for UP (up from 80 now) and 79 for Bihar (up from 40), while Tamil Nadu would add just 10 more seats and Kerala none at all.

In other words, power would be even more concentrated in North India than it already is.

Tamil Nadu Chief Minister MK Stalin has referred to this as a “sword hanging over the South” and even the BJP’s Tamil Nadu leader has opposed a reconstituted Parliament purely on population terms.

Taxation/Representation

Put it all together, and you get the sentiments behind the campaign led by the Southern states:

Massive socioeconomic disparity at the regional level, leading to a significant shift in how tax funds are shared. A vast political divide under the BJP. Deep suspicion that the Union Government will not play fair on inter-state matters. And all of this topped off with existential fears about a major shake-up of Parliament that will seriously undermine the South’s political and institutional influence.

This has allowed Southern states to push the line that the BJP is penalising them for being successful and that Modi’s government cannot be trusted to fairly treat the states it doesn’t run.

The BJP, in return, has attempted to make the more nuanced (and harder to sell) point about intra-state redistribution, while also falling back on its tried-and-tested attack line about the Opposition seeking to “break the nation.”

A few things can be true at the same time here:

Having one vote be worth ‘more’ or ‘less’ in different parts of the country is democratically problematic and unviable in the long run, i.e. the delimitation issue.

Expecting big revenue-collecting states to get back all the funds they generate without redistributing towards poorer states goes against the broader compact of India, i.e. the financial devolution issue.

But, the BJP’s conduct at the Centre and its preference for unilateral moves offers no reassurance that any attempts to address these two longstanding concerns will be done in a consultative, impartial manner.

Given all of that, it is not surprising that the Southern states – and indeed those in other regions run by non-BJP leaders – have sought to push back against the BJP on the federalism plank.

This doesn’t come out of the blue. Ajit Ranade argued back in 2018 that India needs a national discussion about delimitation and federalism. Yamini Aiyar has called for a politics of accommodation between North and South, rather than one of divide. Others have called for the revival of inter-state institutions. Pranay Kotasthane has spoken of a ‘grand bargain’ that would involve abolishing the institution of governor, dividing the state of Uttar Pradesh and reinstating the Rajya Sabha as a genuine council of states, US senate-style.

Yet, aside from its success in bringing in the Goods and Services Tax4, the BJP has offered little indication that it has any interest in broad-based consultations on sensitive issues. Modi’s preference is for grand, unilateral gestures (see: demonetisation, striking down of Article 370, the Covid lockdown, the Upper-Caste economic quota, the Farm laws, the women’s reservation bill5, and so on) with little space for any genuine deliberation.

Given that context, efforts from Southern states to mobilise their support base and build long-term narratives on this issue should be unsurprising.

A few more links on this:

A concise piece by Arun Dev, Divya Chandrababu, Vishnu Varma on what’s driving the my tax, my right protests.

Jasmin Nihalani on why some states get more than others.

Tamil Nadu Minister Palanivel Thiaga Rajan on whether UP’s economy has surpassed Tamil Nadu’s and how his state responds to the redistribution argument.

A set of essays edited by Diego Maiorano and Ronojoy Sen on the centralisation of power and the rise of a new political system in India.

M Govinda Rao’s paper on fiscal decentralisation in India’s federal system.

A pair of pieces by Rathin Roy on the fiscal devolution question.

Of course, the reality is much more complex: There are plenty of non-Hindi speaking states where the BJP thrives (Gujarat, which is Modi’s home state, Maharashtra, Goa, Assam) and it has even held power in one of those in the South (Karnataka). But the broad idea of a North-South divide – in politics, economics and culture – does hold, though of course, that is not, by any means, the only significant regional divide in India.

The first, from 1952-1967 represented immense Congress dominance; the second, from 1967-1989, saw the broad decline of the Congress and growing contestation at the state-level; the third, 1989-2014, was an era of fragmented, regionalised coalition politics.

GST gave India a common market for most goods and services, and was brought in during Modi’s first time after first being thought of two decades prior. Turning it into reality involved genuine consultation and deliberation between the Union and States, one of the rare occasions that the current government chose to use that approach. In limiting the space for states to individually mobilise their own resources, however, it has also played a role in fomenting the federalism crisis.

Interestingly, the BJP may have hoped that it could blunt the South’s pushback by yoking the women’s reservation law – which mandates 1/3rd of Parliamentary and Assembly seats be reserved for women – to the delimitation issue.

The issue of "One person One Vote" and the "Fiscal Delimitation" could be addressed by having clear definitions for the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha. The Lok Sabha should use updated census to make sure all constituencies are of equal size to ensure equal representation. The Rajya Sabha could micic the US sentae with equal representation for all states (or) have a delimitation based on state economy size. We have to ensure all money bills need to be approved by Rajya Sabha, so the richer states would have better say on how to spend the Union's money.

India needs to be decentralized. It is a pity that only 3% of our budget is spent at the local municipality level while China has 45-51% of its budget spent at the local level which makes Chine 16-17x more decentralised than India. This would also increase the % of tax revenue any state can retain. We would also have ability to tax at a municipality level in every state similar to US/UK etc.

PS: Initially you have referred to Thangam Thennarasu as the CM of Tamil Nadu while he is the Finance Minister.