Quick plug: On the Political Cycle, we spoke to MomLeft’s Kelly Weil about the how parents and gender rights fit into this year’s US elections.

Globally, India isn’t often thought about as a country with too few people. After all, it was only in 2023 that India overtook China as the world’s most populous country, with a staggering 1.4 billion people. Yet, headlines were made last week when N Chandrababu Naidu, chief minister of the South Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, announced that his government was considering legislation to that would incentivise couples to have more children.

Naidu’s comments in fact were a nice distillation of the 180-degree turn in the discourse around population in some parts of India, from the Malthusian idea of a population bomb prompting policies seeking to restrict families to just two children, to current worries about too few babies being born:

“We have repealed the earlier law barring people with more than two children from contesting local body elections… We will bring in a new law to make only those with more than two children eligible to contest.”

Where is this coming from?

Data for India’s Rukmini S explains it succinctly:

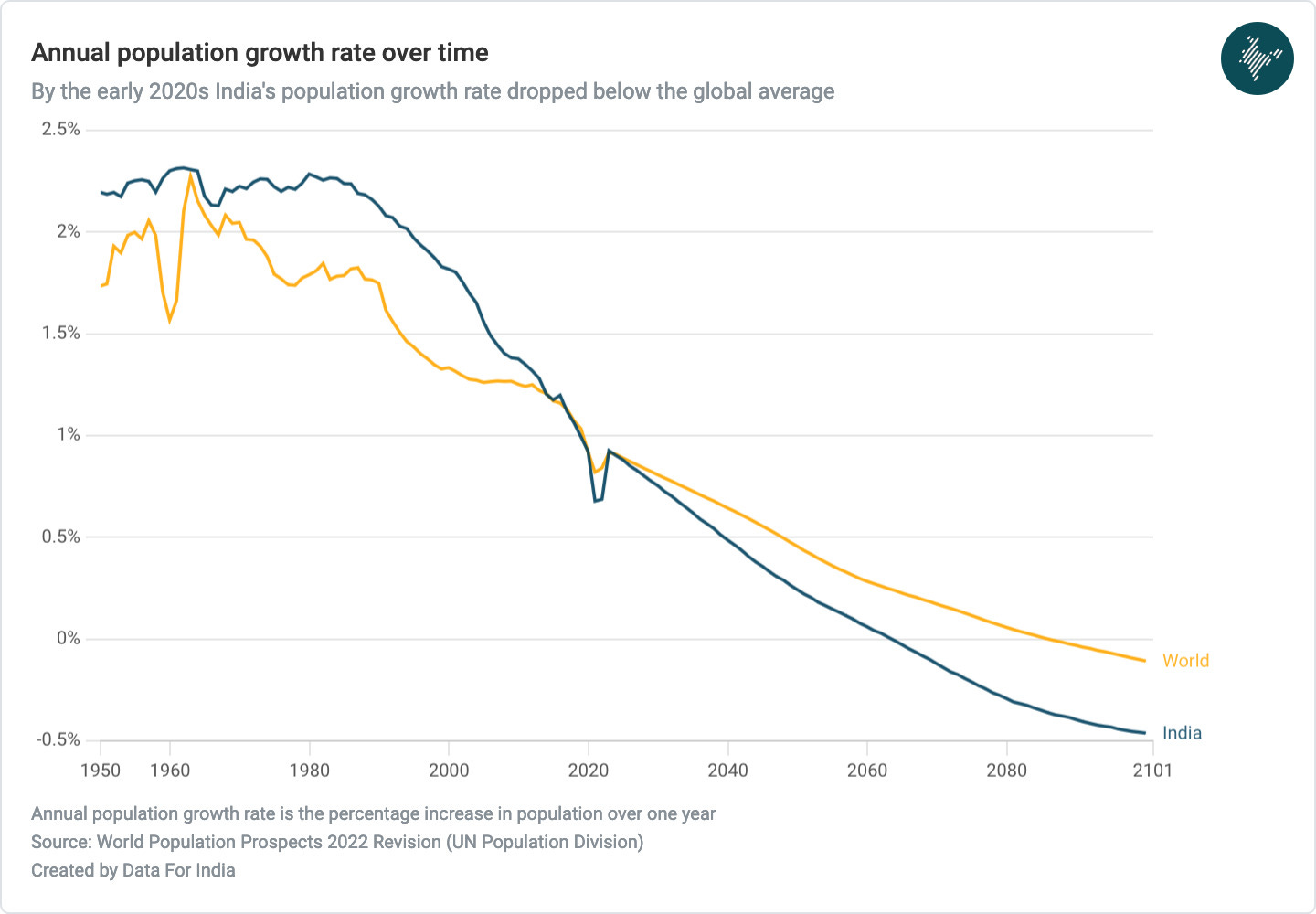

“There was certainly a time when India's population was growing very fast. In the three decades after Independence, India's population had doubled. But from the 1980s, population growth began to slow down. India's population growth rate is estimated to have fallen below the world average by the early 2020s and the gap is expected to grow.”

This is felt particularly acutely in South India, which, for a combination of reasons, saw fertility rates fall much faster in the decades since India began active family planning programmes than North India.

This is quite a remarkable development, albeit one that brings with it plenty of challenges, as demographer Srinivas Goli explained to the Indian Express:

“The same amount of fertility transition – that is to come down from six children to 2.1 children per female adult – France took 285 years, England took 225 years, whereas India took just 45 years. The only country which took less time to reach this fertility transition is China, due to its very rigorous one-child policy,” Goli says, adding that this has left South Indian states “becoming older before getting richer”, unlike the European countries mentioned above, for example.

Goli says that in order to reap demographic dividend – that is a higher working age population and lower dependent population – the dependency ratio should be below 15. “In Andhra Pradesh alone, the dependency ratio is 18 (as per 2021 figures),” Goli says, pointing out that this will lead to more problems in the future due to little support for the older population in the country.”

This idea of an ageing South India has a number of implications – cultural (not least in the large number of North Indian workers moving South), societal (is Indian society prepared to deal with a larger elderly population?), governmental (can healthcare systems keep up?), among others.

One that we have consistently focused on, here on India Inside Out and on my previous newsletter The Political Fix, is the federal element: The distribution of seats in the Lok Sabha has, because of a complex history, been frozen since the 1970s. This has meant that each North Indian Parliamentary constituency is much larger than South Indian ones.

Background to the federal conversation:

Why South Indian states are up in arms against Modi and the BJP

Full-page newspaper advertisements for politicians, parties or governments are an extremely common phenomenon in India. And the figure of ‘Mahatma’ Mohandas Gandhi turning up in these ads is not unusual either. Yet, despite that context, the visual that turned up across newspapers on February 7 was a break from the norm:

Were seats in the Lok Sabha to be redistributed as per the population, South Indian states would see a major dent in their relative political power, with the North getting many more seats than before. Even if such a move ought to happen – since the current situation means votes in the South are much more ‘valuable’ than votes in the North – how can the Indian state carry out this ‘delimitation’ (as the process of redistricting is known in India), without cracking open North-South fissures and threatening the federal compact?

We may be about to find out.

From the Indian Express’ Liz Mathew:

“The government is set to conduct the much-delayed Census next year, and to complete the process by 2026.”

Similar stories appeared in India Today, News18 and elsewhere, though in all cases they were attributed to unnamed government sources.

I’ve written about the delay in the census before, as well as the implications it may have for the question of caste census as well as the women’s bill. These new reports are divided over whether the census, now planned for 2025-26, will include a caste enumeration. (The Express report says the government “has not been able to finalise a formula for” a caste census, whereas News18 claims “the government has no plans to allow caste census.” India Today, meanwhile, suggests that the census may “also include surveys of sub-sects within the General and SC-ST categories”, which would be relevant to the major Supreme Court decision permitting sub-classification of SC reservations).

But they all rather confidently say that the government will carry out delimitation based on the census.

Express: “Following the completion of the Census, the government will go ahead with delimitation, for redrafting of constituencies. Sources said the rolling out of women’s reservation will follow. Both these exercises are linked to the Census.”

India Today: “Following the Census, the delimitation of Lok Sabha seats will commence, and this exercise is likely to be completed by 2028, the sources added.”

News18: “Meanwhile, sources also said that when the publishing of the census data take place, the government will begin the process of delimitation. This will give the country more elected representatives in the coming years. Only after the process of delimitation is complete can the likes of women’s reservation of 33 per cent be implemented.”

If the census is indeed conducted over 2025-26, this may not be a given. That is because the relevant article in the Constitution calls for delimitation to take place based on the first census conducted after 2026. In other words, were the government to go ahead with its plan, it would have to amend the Constitution – a task it has successfully carried out before (see: Article 370, the Women’s Reservation Bill) but made much harder by the fact that the Bharatiya Janata Party’s ruling alliance has a much smaller footprint in Parliament after this year’s elections, and faces a much larger Opposition than it did before.

When the BJP introduced the law that would reserve 33% of Lok Sabha seats for women in 2023, it added the rider that the quotas would only come into place following the next census and subsequent delimitation. Tying the women’s bill to delimitation was seen as a one way to blunt pushback from the Opposition, and it seems likely that this will still be at least one of the BJP’s arguments for going ahead with the census and redistricting. Will it be sufficient to convince 2/3rds of Parliament neeeded to amend the Constitution?

Mathews’ is the only report that touches on both the legal and political challenges of this potentially massive news:

“Sources in the government have said they are aware of the concern, and any measure that could “damage” southern states, which have “made remarkable progress in population control and other social developments”, would be avoided.

A senior Union minister said: “The Prime Minister has made it clear that the delimitation process should not wedge any divide between the North and South. Maybe finetuning or tweaking of population-area formulas could help. There will be discussions with all the stakeholders and a consensus will emerge.”

The amendments required for a delimitation process include changes to Article 81 (which defines the composition of the Lok Sabha), Article 170 (composition of Legislative Assemblies), Article 82, Article 55 (deals with the presidential election process for which value of each vote in the electoral college is decided on the population basis), Articles 330 and 332 (covering reservation of seats for the Lok Sabha and Legislative Assemblies, respectively).”

Presumably, we’ll get more details on the government’s thinking behind this move – and how the Opposition plans to respond, over the coming days.

One interesting tactical note, though is the approach. In Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s first two terms, the government tended to prefer shock-and-awe measures for major policies, essentially relying on ‘fait accompli’ rather than consensus building. Early into his third-term however, Modi had to roll back a number of moves, in part because of pushback from coalition allies. That, however, was before the Haryana victory, which has, reportedly, “enthused a down and out BJP cadre” and changed “even the body language of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.” What then explains the off-the-record, ‘trail balloon’ approach to this census-and-delimitation announcement?

See also:

Implications of India’s Regional Demographic Diversity, by KS James and Shubhra Kriti

‘South India isn’t running out of people. Solution to delimitation is in political action,’ by Nilakatan RS

Busting India’s demographic myths, an interview of Poonam Muttreja, by Milan Vaishnav.

How should South India deal with its aging population? by Udit Misra

Puliyabaazi on delimitation.