What Katchatheevu tells us about Modi and the BJP's calculations

Plus, a new election interview series.

Welcome back to India Inside Out.

We didn’t have an edition last week because I was just settling into my digs at the Center for the Advanced Study of India at the University of Pennsylvania, where I immediately had a chance to attend talks on fascinating new work on India by Karthik Muralidharan, Sudev Seth, Mira Jacob and Anupama Rao, meet the Academy Award-nominated director Shaunak Sen, visit the entirely reconstructed mandapam/hall of a sixteenth-century Krishna temple from Madurai at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and even attend a Penn Masala concert. I’m going to be here for the next month, and will be making visits to New York and Washington, DC over that time. If you’re around and want to catch up – or just have recommendations – send them to me!

With the first phase of elections in India just around the corner there is a lot going on, only some of which I’ll be able to get to myself, so I might be sending link round-ups at a bit more frequent pace than the usual monthly email. If you spotted interesting reportage or analysis, please do send it in and I’ll add it to the links email.

Before I get to this week’s item, a few plugs:

CASI Election Conversations 2024

At CASI’s India in Transition, we have begun a new interview series in connection with the upcoming elections.

Instead of doing the usual who’s-up-who’s-down content, we decided to have in-depth conversations with top political science scholars and observers on what we understand and are still seeking to discover about Indian politics, political economy and democracy as we enter this election period. Over the next two months, we’re hoping to tackle questions about federalism, electoral quotas, voter mobilisation, misinformation, credit attribution and much more.

Up first, Louise Tillin, Professor of Politics at the India Institute, King’s College London speaks to us about Indian federalism and how it has evolved over the last decade.

“If we look back to the 1989 to 2014 era, that period of political regionalization, in many ways, wasn’t actually years in which there was a great deal of strengthening the institutions of federalism or even really articulating the idea of federalism... I think we can really see in hindsight how weakly entrenched the institutional landscape of federalism was in that period of supposedly inevitable federalization.

The other thing that has come into much clearer relief in the last 10 years has been the question of federal design. It's not a coincidence that I and others have been going back to understand the origins of India's centralized model of federalism and trying to recover the ideas that animated that design. But the reality is that the constitution itself, by design, places relatively few checks on a party which has a parliamentary majority, particularly if you think of the design of the Rajya Sabha. India’s upper house looks very different than the Senate in the US or the Brazilian Senate, for instance, where states are represented on an equal basis..

Modi came into office in 2014 talking of trying to create a “Team India” to encourage states to work together in the national interest, using the language of cooperative federalism. I think over time that has really been overshadowed because this is not states working together on an even playing field in order to determine the national interest. This is states being cajoled either through incentives or through coercion to pursue the national interest as defined by the central government.”

Go read the whole thing, and subscribe to the CASI newsletter if you’d like to receive upcoming interviews in the series.

The Election Tricycle

On the podcast this week, we speak about ‘change parties’ vs ‘continuity parties’ and how in this year’s elections, attempts are being made to represent both change and continuity in unexpected ways. In particular, incumbents that have held power for many years now, like the BJP and the Tories in the UK, still have to find ways to promise change to the voters.

Go listen, subscribe and share! And if you want extra Tricycle content – we include a potted profile and listener questions every week – sign up for our premium version here.

Status update

Rohan Mukherjee, whose book on the international politics of status recently won ‘Best book in global IR’ at ISA, argues in a recent piece for Foreign Affairs that “when rising states seek global recognition, they often engage in assertive diplomacy and international conduct that provoke backlash, derailing their ascent.”

He cites the US in the 1850s, Japan in the early 1900s and more recently, China. But he is also speaking here of India, where Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party have – as we have written about – done remarkably well to integrate foreign policy into a domestic political narrative, crafting what Mukherjee says is a self-reinforcing message: “If the party can catapult an “ordinary citizen” such as Modi to global prominence, it can do the same for a country that has languished in poverty and weakness. Similarly, if Modi can make India secure, prosperous, and widely respected, he can do the same for the Indian voter.”

But this skillful fusion of the domestic and the international is not necessarily without costs. Mukherjee writes:

“The expansion of engagement in international relations from the elites to the masses has deeper and more predictable causes. As India rose in power, its population was bound to express a greater interest in international affairs and a greater desire for global respect and recognition. That Modi could fundamentally grasp Indians’ expanding ambitions and channel them speaks to his savvy as a politician.

Yet a nationalist foreign policy does not always serve the national interest…

As New Delhi gains influence, its interests will begin to seriously conflict with those of more powerful governments—including Washington’s. An overconfident public could then become a liability for India’s political leadership, forcing it to magnify minor quarrels with other societies and pushing it toward riskier strategies and more uncompromising stances…

Most modern societies, of course, are nationalistic to some degree. But when foreign policy itself becomes nationalist, it gives rise to self-defeating risks.”

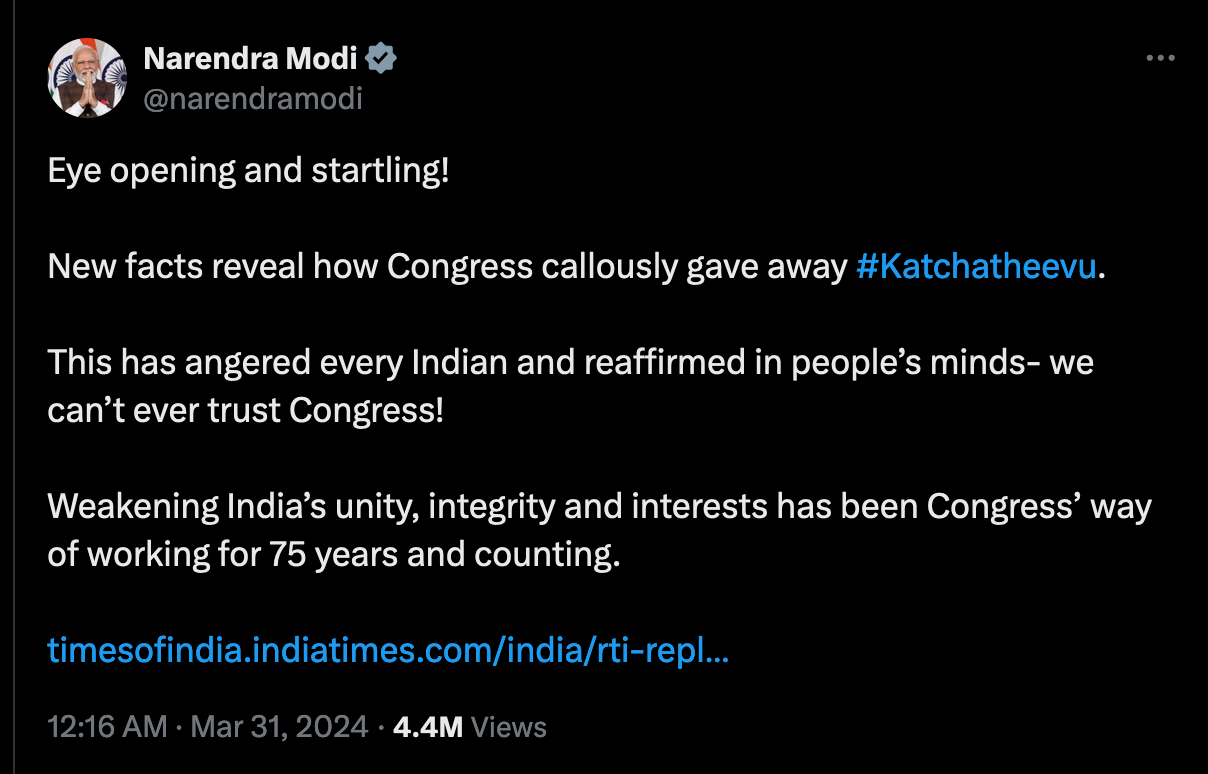

Almost as if on cue, the prime minister brought up Katchatheevu – an island that the government of India officially recognises as belonging to Sri Lanka.

The very next day, External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar also said that the situation was still “alive” and that a solution would have to be worked out with the Sri Lankan government. Sri Lanka, for the moment, has dismissed the issue saying there has been no official communication from New Delhi, and that it considers the matter settled.

Katchatheevu is an uninhabited island that lies between India and Sri Lanka in the Palk Strait, most known for the St Antony church where an annual feast day is celebrated by fishermen of both countries. The dispute over the island, which dates back to well before Independence, was settled between 1974 and 1976 when India recognised Sri Lanka’s rights over it – and the rights of Lankan fisherman to use those waters – while extracting, as Nirupama Subramanian explains, concessions from Colombo elsewhere.

That decision has been controversial ever since, with the dispute being less about the land than the fishing rights – and reemerging as a pertinent issue in the aftermath of the Sri Lanka civil war. As Udayan Das explained in 2023,

“Domestic politics in both countries play a role in not putting the maritime boundary into practice. The politics of Tamil Nadu fiercely supports the cause of coastal seafaring communities. The Indian government has also incentivised mechanised bottom trawling techniques for a higher catch. The Sri Lankan side has rich fishing grounds and the preoccupation of the fishers from northern Sri Lanka with the long civil war allowed the Indian side to intrude into Sri Lankan waters. As Sri Lanka recovered from the civil war and fishing became active in its northern waters, vigilance against Indian fishermen increased, resulting in incidents of seizures, arrests, and killings.”

For more background, read this explainer by Nachiket Deuskar, which also points out that this is not the first time Modi has brought up the issue.

There are several important political elements to consider in the BJP’s decision to bring even more attention to Katchatheevu and treat it as a live issue right now:

The first is, obviously, Parliamentary elections. All of Tamil Nadu’s constituencies vote in the very first of India’s seven-phase elections, on April 19, focusing quite a bit of national attention on the state – one of the southern states where the BJP has long struggled to make its mark, not for a lack of trying.

The second is that Katchatheevu is, at least at the political level, a genuinely live issue, given how often it turns up in rhetoric from Tamil Nadu-based parties, which regularly promise to pressure the Union Government into retrieving the island from Sri Lanka.

Given that context, the BJP’s stance is not surprising as a tactical response to the rhetoric from regional parties, particularly the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK)-Congress coalition that runs the state. As Modi said in Parliament in 2023, “these people from DMK, their government, their chief minister write letters to me. They still write and say, Modi ji bring Katchatheevu back. What is Katchatheevu? Who did it? Beyond Tamil Nadu, and right before Sri Lanka, someone had given away an island to another country. When was it given? Where did it go? … This happened under the leadership of Shrimati Indira Gandhi.”

Indeed, the All India Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) has often more forcefully owned this issue arguing that the DMK was complicit in the 1974 decision to recognise the island as Sri Lankan land – a claim the DMK denies. The BJP, having failed to secure an alliance with the AIADMK ahead of this election, sees the potential for to muscle in on some of the Tamil party’s territory through similar rhetoric.

The BJP is also hoping to use the issue to transform its own reputation in the state. Long seen as a North Indian, outsider presence in the state, the party is desperate to depict the DMK as a dynastic, corrupt, narrowly interested entity (reflecting the image it has constructed of the Congress at the national-leve), while seeking to grab the ‘nationalist, defender-of-the-people’ territory that it comfortably owns in most other parts of the country. Crucially it hopes to do this by side-stepping many other elements of Dravidian politics that it has struggled to confront in the state.

Few expect this issue alone to drive the BJP to bigger gains in the state, yet it is one more brick in a longer-term effort to build its presence while knocking down the edifice of its opponents.

What is also striking is the confidence in which the BJP is willing to wield a foreign policy issue – indeed, one with a mostly friendly neighbour – in its effort to make domestic political gains. Mukherjee argues, in the piece we mentioned earlier, that

“As their power grows, states come to expect that countries ranking below them will defer to them and that countries above them will make room for their continued ascent…

Nationalist diplomacy backed by an increasingly confident and assertive public will also make such issues difficult to resolve by limiting the scope for compromise. Voters, for example, may turn against a government that—having set high expectations—falters in protecting expansive versions of the country’s interests and honor.

National pride may know no bounds, but foreign policy must operate in a highly constrained environment. India’s political leadership will therefore have to work carefully to ensure that its nationalist diplomacy does not undermine national objectives. At the same time, India’s friends and partners will have to adjust to its assertive demeanor—in part, by making room for the country as it ascends in the international order.”

Indeed, Sri Lanka is having to adjust to exactly that. However, at least from the outside, the Indian government appears able to capture all the upside of these political gambits with little of the downside.

In a different climate, one might see such an issue being raised by an incumbent government result in questions about what it has done over the last decade to correct what it now claims is a grave error. Or concerns about having an element of its political campaign hinge on a foreign policy issue that cannot be as easily resolved as domestic ones. Or one might see a reluctance to rake up a relatively soft territorial dispute, for fear of bringing up comparisons with its actions on the other, much more challenging boundary dispute with China in the North (which is indeed how the Congress attempted to respond).

Yet, such is the confidence the BJP appears to be carrying into these elections – not least because it has little fear of being challenged by the mainstream media – that it is able to confidently wave about a complex issue such as this without fear of domestic backlash. At the international level, just as with the Maldives mess and the Canada crisis before that, it is evidently making the bet that India’s continued economic heft and geopolitical significance gives it the space to throw its weight around.

Mukherjee’s argument is that, as time goes, we can expect those bets to get riskier and riskier.

Read also:

Katchatheevu demands thinking outside the box

Ex-diplomats caution government on Katchatheevu

Shekhar Gupta: Understanding Katchatheevu, India-Lanka ties through Nehru, Shastri, Indira, Modi

Speaking of status, an argument from Kaush Arha and Samir Saran: The US needs a new paradigm for India: ‘Great Power Partnership’

Sanjaya Baru: Are India-US relations going into a free fall?

I would rather wish for common sense to prevail and people will vote Modi and his corrupt government out.

It is strange that the present Ext Affaires Minister has forgotten that when the question on this issue was raised in the Parliament in 2015 or 16 when he was Foreign Secretary , he gave a reply on what were the issues discussed when finalising our treaty with Sri Lanka. Obviously he has changed his colours and become a politician and has expressed views to please his present boss! I hope Sri Lanka as a repartee cancels the port project now given to Adani at our PM’s request