Of the many pieces I wrote for Scroll.in over the years, the one that received the most traffic was a short article I put together in 2015 entitled, ‘Everyone in India thinks they are 'middle class' and almost no one actually is.’ The piece relied on survey data that showed the power of the ‘middle class’ brand in India: Practically every income group in the country, rich or poor, prefers to be described as middle class.

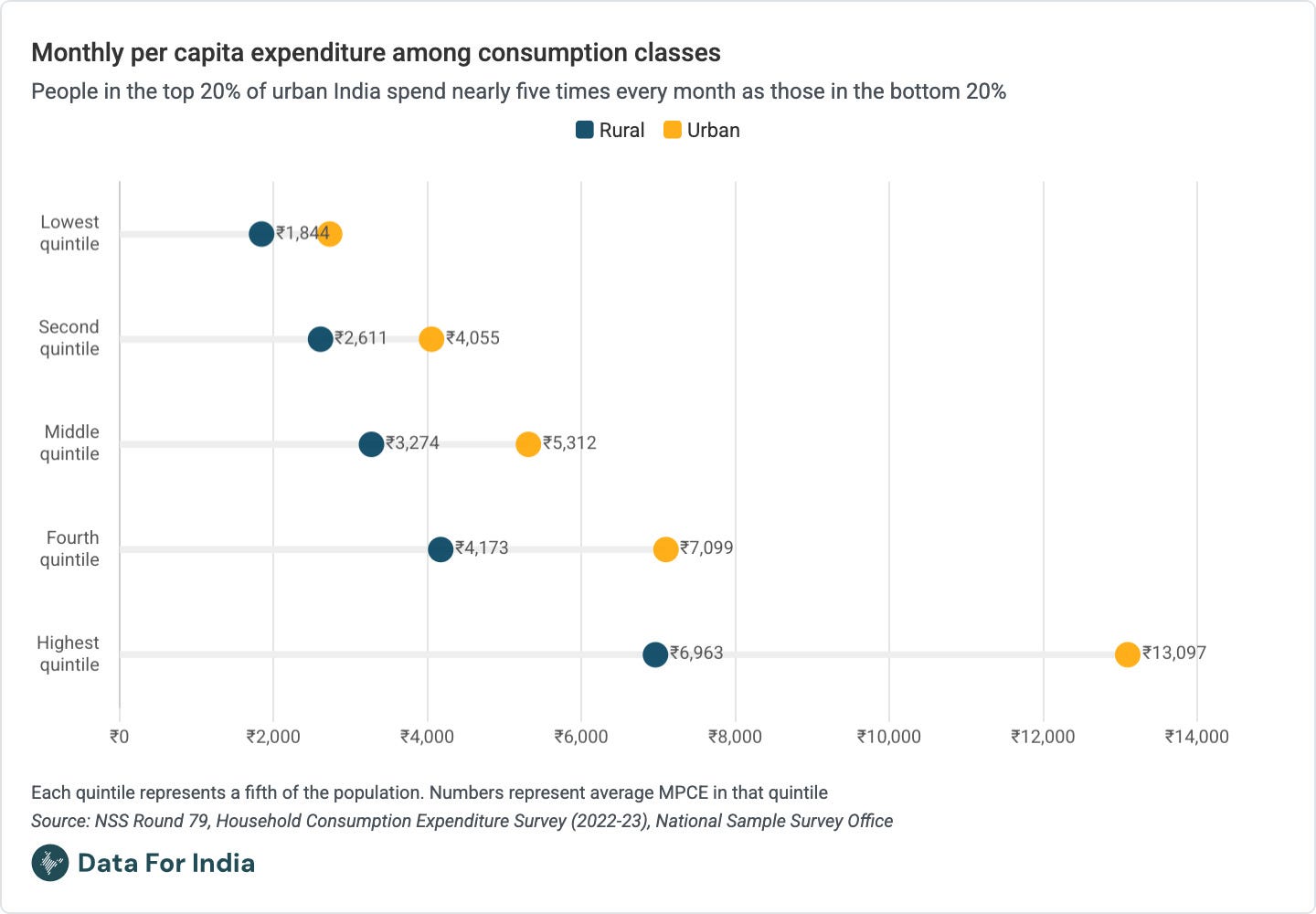

An analysis by Devesh Kapur, Milan Vaishnav and Neelanjan Sircar in 2017 cobbled together 13 different attempts to categorise India’s middle class between 2004 and 2015, with definitions going from just 2% of all households to 40% of all households. One piece written ahead of the tabling of the Budget this year sought to classify individuals earning up to Rs 1 crore (10 million) annually as ‘middle class’, even as expenditure data suggests that people who actually fall in the middle quintile are only spending between Rs 3,274 to Rs 5,312 per month.

The (not necessarily novel) point to be made here is that ‘middle class’ is a rather tricky concept to pin down in India, and one that, as Surinder S Jodhka and Aseem Prakash have argued, should be seen as a ‘historical and sociological’ category, rather than a statistically distinct segment of the population, let alone one that is located at the midpoint of the income distribution ladder.

It is useful to keep this disclaimer in mind when looking at analysis of the Budget, tabled on February 1 by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, widely hailed as directed at the Indian middle class.

“Earlier, the middle class would lose sleep over the Budget. But this Budget has come as a relief,” said Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in a campaign speech a day after the Budget was tabled. “This Budget is the most middle class-friendly Budget in the history of the country.”

The ‘lose sleep’ comment is interesting, given that Modi has been in power for nearly 11 years now and Sitharaman this year achieved the distinction of becoming the first finance minister to present eight consecutive budgets.1 Still, with the budget coming right ahead of elections in Delhi, where the average voter is both wealthier and more likely to be a government servant than elsewhere, some amount of hand-waving towards the middle class was always on the cards. Moreover, over the last few budgets in particular, Sitharaman had received much criticism for appearing to squeeze this segment, even as the poor were receiving cash handouts and the super-rich saw their incomes balloon.

From last year:

In the event, the middle-class focused messaging turned out to not just be cosmetic. Sitharaman, in the final flourish of her 77-minute budget speech, announced an increase in tax exemption limits, which means India will essentially charge no tax on individuals who earn up to Rs 12 lakh, up from Rs 7 lakh previously. That raises the tax exemption limit to five-times India’s per-capita income, a much more generous threshold than in many other countries.

The government is expecting this to benefit about 1 crore (10 million) taxpayers, and, according to a Business Standard calculation using last year as a base, would mean that of 75 million salaried individuals filing tax returns, up to 67 million (89%) would pay no income tax. The government is expecting to forego Rs 1 lakh crore ($11.5 billion) in revenues, at a time when growth has been sluggish.

“I want to thank the honourable Prime Minister because it was his guidance that we keep aside the calculation of revenue foregone and put money back into the hands of people… This category of taxpayers is the one which is helping run the country,” explained Sitharaman, possibly being more candid than she expected to be.

What explains this move, and why now?

I wrote last week of how one of the central concerns for Modi and Sitharaman has been the fact that their public capex-focused strategy to emerge out of the pandemic has failed to crowd-in private investments. More worryingly, questions have begun to be raised about how much capacity remains to absorb additional government spending on this front,2 though Sitharaman remains adamant that capex spending limits have not been reached.3

This, then, would be the simple version of the story so far:

The government gave massive corporate tax cuts in 2019 in response to alarmingly low growth rates before the pandemic hit, though these achieved little. The pandemic then appeared to provide an opportunity to make significant reforms, coupled with a steadfast commitment to fiscal consolidation and heavy capex spending from the government that would power the economy until the private expenditure engine of growth began firing again. An autocratic rather than consultative approach to tricky reforms meant that path was abandoned – alongside other objectives like large-scale privatisation – prompting the entire edifice to rest on the public capex platform.

With this running out of steam, having failed to crowd-in private investment (and unwilling to consider expanding social sector spending), the government began fretting about the demand-side of the equation.4 And so it has decided to intervene directly on this front, effectively hitting pause on public capex plans to deliver some taxpayer relief that might also spur some demand. Alongside this, the government is turning back to a Congress-era idea to catalyse private spending: The Public Private Partnership.

Will the mini pivot-to-demand work? The classic analysis of ‘multiplier effects’ (i.e. how much government efforts can add to overall economic output) found income tax cuts to be much less effective than capital expenditure, though the author has said that it may be more useful during a period when consumption numbers are trending down. Even if successful, though, this tax route to stimulus will remain small.

The real focus now turns elsewhere: The Reserve Bank of India. The central bank’s monetary policy committee will decide, at the end of the week, whether to lower interest rates for the first time in five years. It has the unenviable task of being expected to provide a rate-cut stimulus against the backdrop of a Trumpian global environment where trade and currency volatility has gone through the roof. (Worth noting that the budget also saw import duties on a number of items reduced, read by many as an effort to shed the ‘tariff king’ tag that Donald Trump used for India during the campaign) Even if it were to now lower rates, will that provide enough of a boost to business expectations to make fresh investments in India, when so much else remains uncertain?

Read also:

I am collecting some budget commentary here, with bold emphasis added by me. If there is a useful piece that I’ve missed, send it to me and I’ll plug it in on the next edition:

“In February 2021, the finance minister had announced a plan to gradually bring down the fiscal deficit of the Union government over five years, so that public finances could be repaired without harming economic recovery through a dramatic fiscal contraction. The government has credibly met its promise, with fiscal deficit expected to be 4.4% of GDP in 2025-26. It will now begin to pivot to a new fiscal strategy based on putting the ratio of public debt to GDP on a downward path. It is a fiscal framework that is untested in India.”

“The good news is this is a strong affirmation of the government’s commitment to macroeconomic stability. Fiscal credibility, alongside the war-chest of FX reserves, a benign current account deficit and inflation heading back to 4 per cent, should provide a cushion against external shocks.

But conservatism is not costless. For starters, by over-delivering on this year’s fiscal deficit, the room for spending in the coming months is more constrained. Total government spending (ex -interest) recovered nicely to grow at 23 per cent last quarter. If this year’s targets are to be met, spending will have to slow to just 8 per cent this quarter. Further, a reduction of the fiscal deficit is a withdrawal of stimulus. So next year’s consolidation will be a drag on growth, such that a lot of the heavy lifting will have to be done by monetary policy.”

“The year's top economic policy event opted mainly for short-term economic relief through middle-class tax cuts, while passing up a chance to go big on reforms needed to reignite rapid growth - once the envy of the world at more than 8%.

The budget also scaled back the government's emphasis on capital spending and infrastructure, another key driver for India's growth ambitions since the pandemic.

Without a strategy to regain high growth rates and assure jobs for India's young population, the budget disappointed analysts and markets, alarmed in recent months by weak earnings growth and an exodus of foreign investors.

"India is aspiring for 8% growth but we don't have a path to 8% - a growth strategy is not there," said Madhavi Arora, chief economist at Emkay Global Financial Services.”

“This is, in effect, a budget that marks time, preparing for a shift in strategy from state-funded growth to private sector-funded growth, by reviving the public-private-partnership (PPP) model that the previous UPA government had used effectively to keep the share of gross fixed capital investment in the economy at 33-35% of GDP. Post-the UPA, the GFCF/GDP ratio has mostly stayed below 30% of GDP and touched 30% only briefly.

If the budget just marked time, voters would not be pleased. So, the budget doles out tax breaks to the middle class, and hopes that no one would notice that nothing much is being done to boost growth…

The NDA reviled PPP, and relied on direct state funding to boost economic growth. Now, it is changing tack, and that is welcome. But growth is not a spirit that can be summoned by chanting a mantra, even a powerful mantra like PPP.”

For India that is Bharat, the headline feature of this budget was the same as every pre-Covid budget since 2016: GoI remains severely constrained for fiscal space and has yet again shrunk in size. The total expenditure (TE)-GDP ratio — measuring government spending (read: activity) — shrank from 16.03% in FY22 to 15.04% in FY24 to 14.19% in FY26 (BE). It’s now just a percentage point higher than in FY20, the Covid splurge having played out and fiscal constraints having resulted in continuous downsizing. The tax-GDP ratio is stagnant at about 7.9% for the last three years. It is, therefore, expenditure cuts — and only expenditure cuts — that have allowed GoI to maintain fiscal consolidation. Planned reductions in the fiscal deficit-GDP ratio are exactly equal to the expenditure cuts…

Outlays on education and rural development have stagnated, the former at around Rs 1.2 lakh cr, the latter at around Rs 2.5 lakh cr. Deploying the Rs 1 lakh cr revenue foregone (RF) for either or both of these sectors would have made a huge difference to the common person. Instead, GoI has provided tax cuts to the top 10%, and even added top-up freebies for the super-rich in the form of reduced import tariffs on yachts and cars costing above $40,000.”

“What one would therefore have expected from this Budget if it was to make a difference to growth and equity is big spending towards schemes such as MGNREGA along with newer schemes for small and labour-intensive projects, supported by enhanced spending on the social sector. However, budgets for most of these schemes and departments (education, health, social security pensions, mid-day meals) are either stagnant or have increased nominally… Obviously, spending has been cut. Once again the target of these cuts is the social sector.”

There is a crucial element still lacking in the Budget: a comprehensive strategy for economic growth without which tax cuts will not be enough.

Gupta said that for him the biggest problem was the lack of income growth in the country. Tax cuts can provide an initial fillip — a cut in GST would have been better — but they cannot on their own sustain consumption if economic growth doesn’t happen…

Arguably, if the government’s policy intervention sequencing was reversed — income tax cut first and corporate tax cut later — the results could have been different.

Swaminathan S Anklesaria Aiyar:

“Year after year, official documents speak of the need to expand the tax base. But raising the tax exemption limit from ₹7 lakh to ₹12 lakh will contract the tax base substantially. In numbers, the bottom of the taxpayer pyramid is far larger than the peak, and it is the base that the Budget has eroded. This may be good politics but not good economics.

It is also good politics for Sitharaman to show much she wants to do for Bihar, which has an assembly election later this year. So her Budget speech promised new greenfield airports for the state apart from expanding the Patna airport, help for the West Kosi canal, a tourism focus on Buddha (which must include Bodh Gaya), a National Institute for Food Processing, a Makhana support mission for a product Bihar is famous for, and an expansion of Bihar’s IIT.

She promised a new income tax Bill next week, puzzlingly close to her Budget. Why was it not included in the Budget?”

On this, see also Somnath Mukherjee’s piece.

“Of the five promises Ms Sitharaman had made in her July 2024 Budget, she has delivered on four. The unified pension scheme would be rolled out from April 2025. Customs rationalisation has been undertaken, resulting in a cut in the Customs duty on 26 items (including motorcycles), a lowering of the effective as well as tariff rates for 14 items, and a reduction in the tariff rates for 37 items. A new income-tax regime is in place. A debt-anchored fiscal consolidation programme has been unveiled. The only thing that remains to be outlined in detail are the contours of an economic policy framework to initiate fresh second-generation reforms in factor markets, even though there are many references in the Budget on reforms of power distribution, urban sector, regulatory architecture, mining, taxation and insurance, where the foreign investment cap was raised to 100 per cent.”

“The most audacious and positive statement in the Budget lies in the domain of politics and strategic affairs. It is the intention to amend the Atomic Energy Act and the Civil Liability on Nuclear Damage Act. Read this with the target of 100 Gw (1 Gw is 1,000 Mw) nuclear power by 2047. Read it also with the quick adjustments forced by the return of Donald Trump.

If he’s transactional, what will India offer as “give” in return for any “take”?

Only Morarji Desai has presented more budgets than Sitharaman – 10 – though he did so over two separate terms in the ministry.

See this analysis by SC Garg, former finance secretary:

“The government did pump in large Capex funds in the third quarter (Rs 2.7 lakh crore) to bring the nine-month Capex growth into the positive territory. A good part of this fund push took place in two sectors – road and loans to states, which unfortunately did not lead to the real Capex.

Of Rs 2.72 lakh crore in Budget 2024-25 for the road sector, the government pumped in Rs 92,131 crore in the third quarter only taking the road sector Capex to Rs 2.33 lakh crore, achieving a budgetary utilisation rate of 85.5 percent, which is very impressively optically.

Did this fund push lead to more road construction? No.

As reported in the newspapers, NHAI pre-paid its loans of Rs 56,000 crore (out of outstanding loans of Rs 3.35 lakh crore) in the third quarter using government Capex funds. The capital expenditure takes place when you construct more roads not when you repay the loans.”

"Capex is also continuing. I’ve not foregone capex to give for revenue expenditure or consumption expenditure, so both continue.

Over the last year, analysts and voices from industry have been warning about a squeezed, or even shrinking, middle class, with urban consumption showing signs of distress. Chief Economic Advisor V Anantha Nageswaran has, on multiple occasions in recent months, including in the Economic Survey tabled the day before the Budget, pointed out how profitability in the private sector is at a 15-year-high, but wages have remained low – impacting aggregate demand.

I’m sure there are significant differences, but the idea of most Indians thinking of themselves as middle class is strikingly similar to how Americans see ourselves. Many truly affluent Americans don’t realize how rich they are, and the line between middle and working class has been blurred in the United States since about the middle of the twentieth century.