'Peak Modi', post-Modi, 'Adani-Ambani' and other notes from the Indian elections

Plus, another Election Tricycle episode.

Welcome back to India Inside Out.

On this edition, I have just a few scattered notes from this year’s Indian elections before we break for a couple of weeks, returning after the results come out on June 4.

Before we get to the notes – and not actually full pieces, because I’ve been busy conducting the CASI Election Conversations 2024, an interview series on Indian politics and democracy that we ran on India in Transition – a link to this week’s episode of the Election Tricycle, on which we discussed the economy, economic confidence, and statements from India’s Home Minister and External Affairs Ministers attempting to calm the stock markets in response to what appear to be election-time jitters.

Listen, subscribe and tell people about our little podcast!

On to the notes:

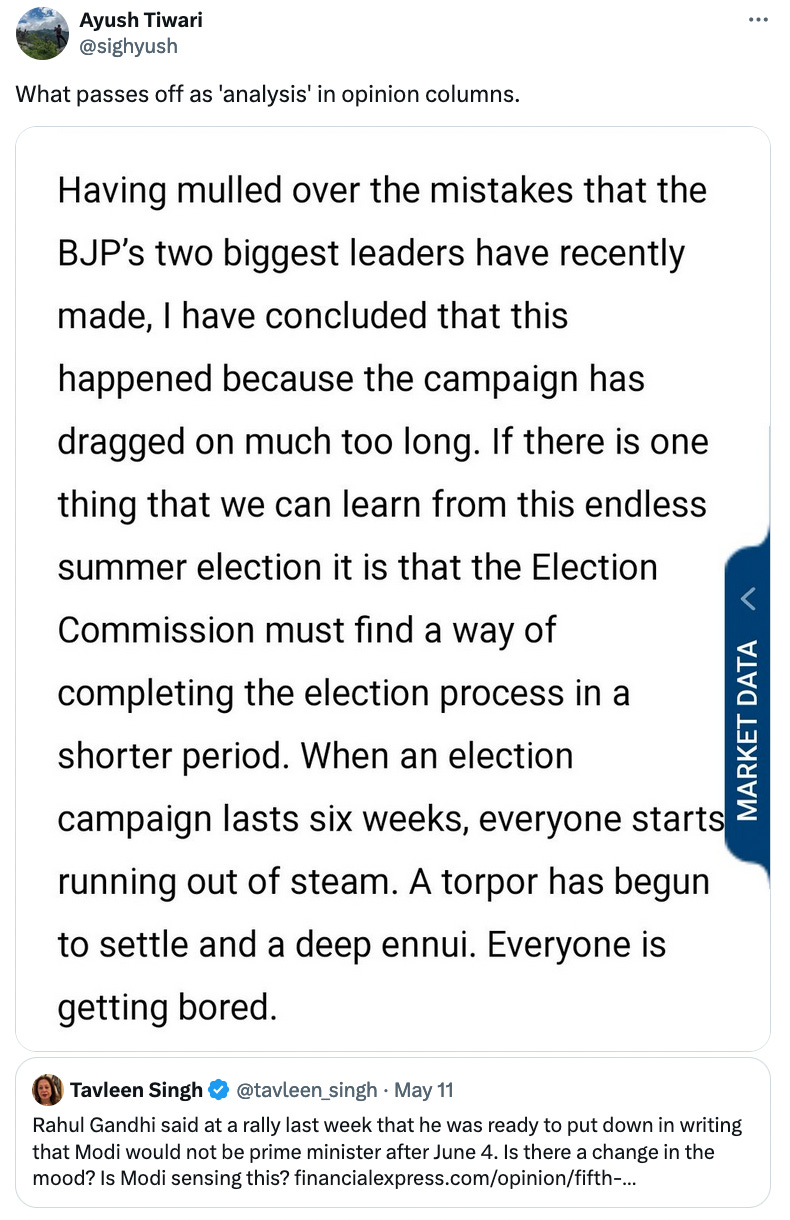

‘Election Boredom Hypothesis’

On the premium edition of the Election Tricycle – which you can sign up to here – we spoke about a boredom theory for Indian elections, as propounded by Tavleen Singh.

With due credit to Matt Levine, I think there is a boredom theory for Indian elections, but it’s misguided to attribute that to politicians, who may be exhausted (or frustrated, or angered) by the relentless campaigning but I doubt are sliding into a “deep ennui” over them.

Instead, I think the boredom is more likely to come from observers (journalists, commentators, political consultants, etc) who are less invested in individual battles taking place all over the country – which are not boring by any measure – and are simply waiting for the national picture to emerge.

It is innate human nature to want to tell stories that feature conflict, or at least that don’t repeat the same narrative over and over again (‘BJP is the overwhelming front-runner’) and so it was almost inevitable that, as we went from phase to phase in this election, there would be talk of the party struggling – even though all the polling and commentary in the run-up to the elections was less about whether the party would be winning and more focused on the question of how big Prime Minister Narendra Modi would be.

This is not to say that some of the commentary is misguided, or that the BJP has not been changing tack. A couple of weeks ago, this newsletter too attempted to read the tea leaves emerging from the first couple of phases, including lower turnout numbers and a sharper tone from the ruling party. Instead, the danger lies in over-reading otherwise valid indicators from phase to phase, and taking those to reflect the likely overall result, when they may be telling us a more nuanced story about campaign effects, regional narrative choices or indeed, organisational dysfunction. (A look back at plenty of mid-election commentary back in 2019 might be instructive).

‘Adani-Ambani’

Why did Prime Minister Narendra Modi attack India’s richest businessmen – generally identified as supporting his platform – in a campaign speech?

Aakash Joshi describes Modi’s unexpected salvo (emphasis added):

“PM Modi’s rally in Telangana earlier this week began predictably enough, with attacks on Congress and Rahul Gandhi. As he brought up the latter’s obsession with business houses, it seemed that it was a prelude to — as in the past — a defence of entrepreneurship and “job creators”. “You would have seen that the Congress shahzada1 (referring to Rahul Gandhi), for the last five years, has been repeating this. Ever since his Rafale row was grounded, he started repeating this — first, he kept speaking of five industrialists, and then started saying Ambani-Adani, Ambani-Adani, Ambani-Adani,” he said. But in a twist, the PM almost echoed his bete noir: “The shahzada should declare — during these polls, how much have they taken from Ambani-Adani (kitna maal uthaaya hai)? How many sacks of black money have been taken? Have tempos full of notes reached the Congress? What’s the deal that’s been struck (kya sauda hua hai)?”

This was an abrupt move, one that many – including the prime minister’s supporters –have struggled to understand. Modi’s party has generally spoken of the need to not demonise ‘wealth creators’ as they claim the Congress and other parties have typically done, and the business groups run by Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani have broadly been seen as partners in the aspirational narrative put forward by the BJP. The latter in particular has been associated with Modi since his time as chief minister in Gujarat, and has seen his companies’ fortunes rise alongside the prime minister’s own political success.

Other BJP leaders have been unable to explain why exactly Modi made these comments, and why he hasn’t repeated them since – despite a muddled subsequent effort by the prime minister to insist that he still supports India’s wealth creators, without addressing the substance of his earlier remarks. Theories, conspiratorial or political, about Modi’s comments abound. So why did he imply that Adani and Ambani were delivering illicit cash to the Congress? To whom was the message intended?

If Modi doesn’t return to the subject, we’re unlikely to ever know for certain. It may not be a coincidence that Modi made his comments in Telangana, a state that the Congress won in assembly elections last year, and whose new government has managed to sign deals with these business groups. But on the face of it, and at the political level, the attempt to co-opt a stock Congress attack against himself, reminded me of a column earlier this year by Mihir Sharma (emphasis added):

“For many Indians, even those who may not vote for the BJP, their prime minister is now one part king, one part high priest, and one part Mister Rogers…

This makes him impossible to run against. Criticism about political stances or policy decisions simply doesn’t stick to someone who refuses to be bound by such mundane considerations. Modi presents himself as more welfarist than those to his left, more nationalist than those to his right, and more globalist than the liberal center.

The prime minister is a master at selling such political contradictions. One day he will say Indians need to rise above caste-based mobilization, hoping to appeal to upper-caste voters tired of identity politics. The next day his party will promise individual caste groups the recognition and concessions that they want. Voters appear undisturbed by the inconsistencies.

Opposition politicians are left disarmed and outmaneuvered. Every single possible narrative — the economy, national security, climate change, jobs, corruption, public services — has already been colonized by the incumbent, leaving them no line of attack.”

The point about contradictions was also brought into focus last week, when Modi insisted that he would not be fit for public life if he ever brought up ‘Hindu-Muslim’ matters, i.e. stoke religious division – despite all evidence of him doing exactly that.

Both of these might be Modi’s most audacious bids yet to blunt Opposition attacks by attempting to boomerang them back at his opponents. Does anyone, supporters or critics, believe either the prime minister’s claims on the religious front or his attempt to be seen as taking on India’s biggest business groups over crony capitalism?

(An interesting side-note here is a preliminary finding by political scientist Sumitra Badrinathan in research on support for vigilante violence in India, where even an admonition against such action, by the prime minister, was not taken seriously by his supporters – perhaps because they assumed that the PM’s comments were a deliberate facade and didn’t necessarily reflect his actual views).

Peak Modi?

When does India hit peak Modi? By that I mean, at the national-level, what point in time represents the peak of the Modi phenomenon, which has given India its biggest Parliamentary majorities in nearly four decades?

In 2014, Modi’s BJP won 282 seats in the Indian Parliament, out of 543. In 2019, it won 303. Going into the 2024 elections, opinion polls suggested a huge imminent victory for the BJP and its allies, riding major victories in three North Indian states in the months before the General Elections, and an Opposition that appeared to be in shambles.

Indeed, before phase 1, one might have assumed that 2024 was likely to represent peak Modi2 – most forecasts predicted a better result even than 2019, and most reasonable analysis would conclude that that 2029 (with Modi at 78, and 15 years of anti-incumbency) would likely be a tougher challenge.

Were the BJP to assume 2024 was likely to be Peak Modi, how best then should they have utilised their ultimate political trump card before began losing value?

One answer would be to go out and maximise gains all over the place, pulling off a record victory that might give the BJP a mandate for fundamental, systemic change that might entrench right-wing dominance over the political system and address –things like women’s reservations,3 simultaneous elections and North-South delimitation, if not the more controversial changes to the Constitution that have long been demanded by a section of the Right.

And that was indeed what the BJP was discussing internally. In December 2023, Modi reportedly told the party that workers should aim for a vote share of more than 50% in these elections, which would be the highest-ever, beating even the Congress at its peak. Home Minister Amit Shah has spoken repeatedly of how the party should capitalise on Modi’s popularity to deliver an “unprecedented” victory and expand in areas where it has struggled in the past.4

This deliberate positioning of a maximalist outcome has, at least in some quarters, appeared to backfire. After phase 1, BJP leaders have repeatedly had to come out and insist that they do not intend to change the constitution, and for a while, Modi stopped speaking of a 400+ seat victory for his alliance. Meanwhile, the mobilizing issues that the party was expecting to rely on – the consecration of the Ram Temple being the most prominent one – appear to not have worked quite as strongly in getting people out to the polls.

Rather than fear of losing, could it be this sense – that the party is in danger of frittering away a ‘peak Modi’ opportunity – explain the shrillness of the BJP campaign, particularly its anti-Muslim tenor, as well as seemingly haphazard messaging, like the Adani-Ambani comment mentioned above?5

Roshan Kishore describes something similar, with a vital point on welfare, in his attempt to explain the tone of the BJP’s campaign (emphasis added):

“With the ruthless yet grounded political beast that today’s BJP is, it is reasonable to assume that it did not do anything special for the elections because it did not see the need for it. There was good reason for the BJP to have such confidence…

A lot of elections from the BJP’s 2017 and 2022 victories in Uttar Pradesh, 2019 Lok Sabha included, were attributed to the party’s superb weaponisation of welfare benefits…

This cohort of beneficiaries has been getting something tangible from the Modi government before every major election. It began with toilets and LPG cylinders before the 2017 Uttar Pradesh elections, continued with PM-KISAN transfers before the 2019 elections and culminated with extra ration under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojna in the aftermath of the pandemic. The last one was a big campaign point in the 2022 Uttar Pradesh elections.

This supply line, barring the reduction in LPG prices, has been largely dry after the 2022 elections in Uttar Pradesh. Has this welfare flow vacuum given an opportunity to the opposition to push in a narrative which talks up economic distress and better welfare promises and then exploits local-level factors to stage upset in some constituencies? Did the BJP err in pushing on the fiscal consolidation paddle in the interim budget? Would things be better for the BJP had it done something like a nominal revision in PM-KISAN payments? Modi could have talked it up in his campaigns…

Speaking of Peak Modi…

Post-Modi?

Every so often, Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal offers a reminder of just how sharp his political instincts – at least on the attacking front – are. Soon after being released on interim bail following orders from the Supreme Court, the head of the Aam Aadmi Party fired this salvo:

“These people ask INDIA bloc about prime ministerial face. I ask BJP who will be their PM? Modi ji is turning 75 on September 17 next year. He himself made the rule in 2014 that people aged 75 will be retired,” Kejriwal said. “He will retire next year. He is seeking votes to making Amit Shah the Prime Minister. Will Amit Shah fulfil Modi ji's guarantee?”

Making it clear how much of a nerve this touched, Amit Shah immediately had to issue a statement insisting that “it is not written anywhere in the BJP’s constitution that you have to retire. Modi will complete the term and will continue to lead the country even after 2029.”

Kejriwal went further:

“The entire country has trust that Modi will not break his rule of retirement age at 75. The stage has been set for Amit Shah to be the prime minister. For him, the BJP has sidelined every challenge like Shivraj Singh Chouhan, Dr Raman Singh, Vasundhara Raje, Manohar Lal Khattar, Devendra Fadnavis. Now the only challenge is Yogi Adityanath who will be removed within 2-3 months.”

Rather than directly attacking either Modi or Adityanath, Kejriwal chose instead to amplify rumours that Shah is unhappy with the Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister’s popularity and would be “removing” him soon. The 51-year-old Adityanath is generally mentioned after Shah (59), and sometimes ahead of him, in survey questions about who might lead a post-Modi BJP.

Kejriwal’s line of attack attempts to leapfrog the ‘peak Modi’ question and go straight to the post-Modi one, making voters wonder if they really want to empower Amit Shah – while also depicting him as personally greedy for power.

The line of attack may only go so far in this election, but it sets up a complicated dynamic for the BJP. As the Economist wrote this week:

“Mr. Modi is [the BJP’s] greatest asset. Around a third of those who voted for the BJP in 2019 said that they did so primarily because of him. This also makes the party vulnerable: surveys suggest that without Mr Modi at the helm, its support could drop to within striking distance of the opposition. And the BJP has long trumpeted its meritocratic culture in contrast to the Gandhi family’s dominance of Congress, the main opposition party.

As a result, the BJP needs to start raising the profile of potential heirs in preparation for Mr Modi’s retirement (or sudden ill-health). With several candidates in the running, though, it must tread carefully to avoid internecine conflict. Mr Modi also has an interest in picking a competent heir to preserve his legacy. But like other strongman leaders, he must be wary of anointing someone who could turn him into a lame duck. “The BJP is in uncharted territory,” says Gilles Verniers of Amherst College in Massachusetts.”

Over the 2000s, Modi was successfully able to first court a strong support base within the BJP, while also building out the ‘Gujarat model’ narrative that gave him a national appeal when he finally was anointed the party’s candidate. In an era of ‘vishwas politics’ and centralised credit-claiming, it has become much harder for any internal BJP player to assume a larger role, except through anti-Muslim rhetoric or extra-judicial policing.

Given the BJP’s overweening dominance, efforts by various would-be successors to position themselves for a post-Modi scenario were always likely to come with much more scrutiny of their internal manoeuvering than the former Gujarat chief minister had to himself deal with. Now with Kejriwal bringing the matter squarely into the public eye, attempting to engineer a smooth transfer (if indeed, that was on the cards, at some point) has only become even more complicated.

Read also:

Election 2024 and the politics of anti-Muslim discourse, by Hilal Ahmed

M Rajshekhar’s essay on the era of BJP dominance, and its relationship to capital over that period.

Neelanjan Sircar and Yamini Aiyar on the interesting role that social media, particularly YouTube, has played in this election, and how the mainstream news media factors into it.

Shephali Bhatt on the YouTube election.

Atul Dev writes a profile of Amit Shah, and includes this terrific anecdote about how surreal it can be to report in Delhi.

Varghese K George pits subaltern Hindutva against a (missing) subaltern secularism. Roshan Kishore argues that this is a misreading of the internal Congress dynamic.

Can’t Make This Up

Liz Chatterjee points to amazing anecdotes from Pranab Bardhan’s new memoir, including this:

Also:

Thanks for reading India Inside Out. I might pop up again to plug work elsewhere, but otherwise, expect the newsletter to be back next after results are out. Send all feedback, suggestions and ‘Can’t Make This Up’ links to rohan.venkat AT gmail.com

Meaning ‘prince’ or ‘royal scion’.

Now some are more inclined to suggest that Peak Modi may even be behind us, though we have to wait at least until June 4 to gauge that.

A 1/3rd quota for women at the national and state-level was already passed by Parliament, in a surprise BJP move in late 2023, though its implementation was deferred until after a census and delimitation.

We touched on this also when discussing the BJP’s last-minute efforts to clinch alliances in a number of states.