On the Political Cycle, we talked about the Indian Supreme Court’s verdict on bulldozing, and how that may have echoes with Trump’s America, the UK and beyond.

If, like many, you have jumped the Twitter ship and made your way to BlueSky, you can find me here.

Do strategic ties between countries have to map the trajectory of economic relations?

That (deliberately simplistic) question applies quite evidently to the two big foreign policy challenges that India will have to tackle over the next few years: How will New Delhi deal with a Donald Trump-led USA? And how will its China strategy develop alongside this?

In some ways, the two arenas present India with a mirror image: It has a growing, bipartisan strategic and defence relationship with the United States, but in Trump’s first term, it also engaged in what observers called a “mini-trade war”, one that may be relaunched when the former president returns to the White House. Meanwhile, New Delhi continues to see China as its biggest geopolitical challenge – notwithstanding recent moves to disengage along the disputed border – yet the Indian government is also under pressure from industry at large and economic thinkers about the need to open up to Chinese capital and businesses.

And the two issues are naturally intertwined: A trade war with even a friendly US might force Indian policymakers to reconsider certain positions on China, especially given troubling recent indicators and talk of a shrinking middle-class.

On the US front, New Delhi isn’t panicking. As many, including External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar, have noted, India hasn’t been struck by the nervous jitters plaguing other American allies following the Trump victory. Some of Trump’s Cabinet picks, including Marco Rubio for Secretary of State1, Mike Waltz, who has been nominated National Security Advisor2 and Tulsi Gabbard as director of National Intelligence3, add to India’s quiet confidence, especially on the geopolitical side of things.

It’s important to remember that President Joe Biden’s administration didn’t majorly back off from Trump-era moves against India, so New Delhi has now had quite a bit of experience with the frosty-economics-warm-geopolitics stance – though a 60% tariff raise on Chinese goods and a 10% blanket one against all imports from the US would reshape global trade in ways that are hard to foresee. That said, at least one brokerage has already concluded that India is likely to be among the “least exposed” of markets to Trump trade actions.

The question of how to tackle China appears to be a bit more unsettled.

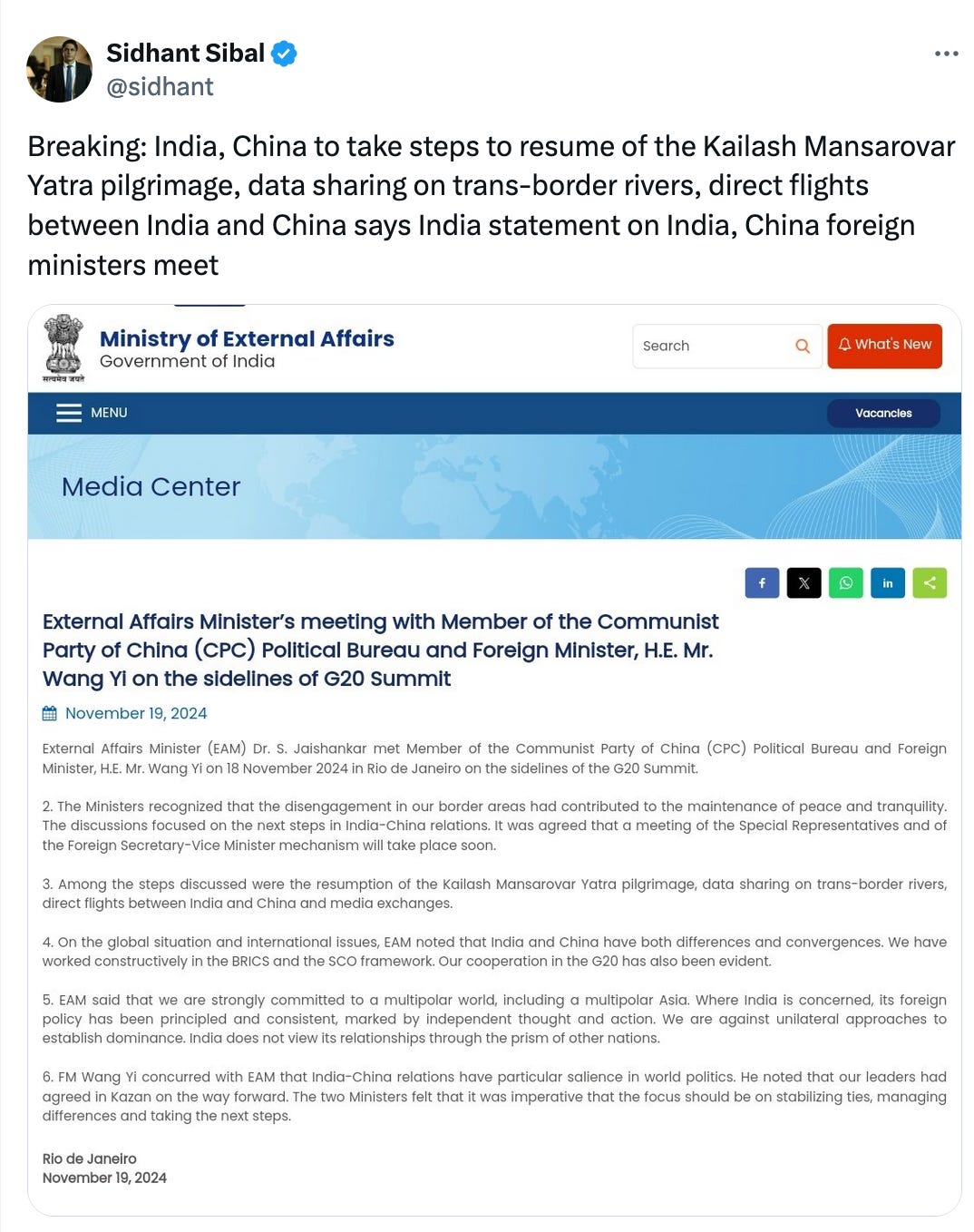

On the geopolitical front, the disengagement of troops along the face-off points that emerged after the clashes in Eastern Ladakh in 2020 has usefully lowered tensions, yet all the core concerns that led to the conflict between the two countries remain.

As former Indian ambassador to China, Ashok Kantha, explained,

“Structural problems in the relationship that predated Galwan haven’t gone away. Indeed, they have become more acute. Prior to the pandemic and developments in eastern Ladakh, India had sought constructive engagement with China and progress was made in some areas. However, in parallel, outstanding issues in the relationship were accumulating…

There was a growing feeling in India that China was not supportive of the rise of India. Bilateral trade was becoming more and more asymmetrical. In 2023, India’s bilateral trade deficit crossed $105 billion, with unhealthy dependencies on China for key imports.

None of this has changed. China is still seen as undermining India’s vital security and strategic interests in the shared periphery. It pays lip service to multipolarity but seeks a unipolar Asia dominated by it.”

Indeed, even on the disputed border the recent deal is just the first part of a more complex process, as Jabin Jacob pointed out:

“This is only, in the Foreign Ministry’s words, a disengagement process. De-escalation and de-induction, as the Foreign Secretary pointed out at Kazan, are steps for the future that will be taken “at an appropriate time”. So that’s not happening yet. We still have to first and foremost operationalise these patrolling arrangements in Depsang and Demchok. The next step would be to operationalise patrolling arrangements or the removal of the buffer zones in the other five friction points.”

In fact, we may have to until next year to even evaluate how well this disengagement process has gone. Yet there are many other signs that what was frosty is now thawing.

These moves have raised hopes of warmer ties on the economic front, but not everyone agrees that this ought to be the way forward. Here are Harsh V. Pant and Kalpit A. Mankikar in Foreign Affairs, this month:

“[New Delhi’s] willingness to see China as both a security threat and an economic boon will hurt India. It is the Achilles’ heel of India’s China policy. Dependence on China for critical components and equipment makes India vulnerable to price gouging, especially during emergencies. Giving leeway to China in the economic realm will have several other costs: it tarnishes India’s image as a rising power that can withstand Chinese coercion, undercuts the notion that India can serve as a bulwark against Beijing’s expansionism, and threatens initiatives that include India in the task of rebuilding supply chains outside China. And India’s forgiving economic policy toward China may encourage smaller regional countries such as Bhutan, which is a strategic buffer between the two powers, to seek accommodation with China—to India’s inevitable detriment.

Indian policymakers must reckon with the dissonance of the government’s tough line on the border and its more permissive approach to economic ties with China. Security and economics cannot be put in silos.”

The piece is a response to arguments from a number of voices in India over the course of this year calling for a loosening of restrictions on Chinese capital and investments. The question was raised quite directly in the Economic Survey, a document prepared by Chief Economic Adviser V Anantha Nageswaran, which offers prescriptions that are not binding on the government.

“The questions that India faces are: (a) Is it possible to plug India into the global supply chain without plugging itself into the China supply chain? and (b) what is the right balance between importing goods and importing capital from China?

…

Replacing some well-chosen imports with investments from China raises the prospect of creating domestic know-how down the road. It may have other risks, but as with many other matters, we don’t live in a first-best world. We have to choose between second and third-best choices.

In sum, to boost Indian manufacturing and plug India into the global supply chain, it is inevitable that India plugs itself into China's supply chain. Whether we do so by relying solely on imports or partially through Chinese investments is a choice that India has to make.”

In the aftermath of the recommendation to open up to Chinese investments, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said she “wasn’t disowning” the suggestion, though soon after Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal said there was “no rethinking” on the question. Sitharaman has since given a vague statement about how India “cannot blindly receive foreign direct investment because I want money for investment, forgetful or unmindful of where it is coming from.”

This back and forth of comments has continued, most recently on the question of joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a trade deal that India significantly stepped away in 2019 from after 7 years of negotiations. BVR Subrahmanyam, chief executive officer of NITI Aayog, the government’s think tank, said earlier in the month that India should be a part of RCEP. This, however, was followed by a statement again from Commerce Minister Goyal that the RCEP was nothing but an “FTA with China”, something he suggested India did well to avoid.

Some have cautioned about even having this debate out in the open, suggesting that it indicates weakness and disunity on the Indian front. Sanjaya Baru disagrees:

“The CEA has set the cat among the pigeons, complained a former Indian ambassador to China, in a newspaper column, questioning the wisdom of exposing to public view the differences within government…

First of all, no harm is done if the world and China find out that this issue is being seriously debated within the government. In all democracies such internal policy differences, even those pertaining to national security, are quite openly discussed. The ministry of external affairs and the office of the national security adviser have no monopoly over national security. The Prime Minister is entitled to balance their views against those of the finance ministry and the ministry of industry and commerce…

More importantly, this issue raises the question as to what really constitutes national security. Is securing territory along the border the sum and substance of national security? Should one not regard as equally important the pursuit of policies that sustain economic growth, enhance investment and exports, generate employment and promote development. Should the settlement of the border issue alone override all economic considerations that aim to strengthen the foundations of economic growth?”

Given that Trump Round 2 is just about to kick off, expect the China question to be even more front-and-center over the next few months than it has been over the past four years.

Read also:

“Work to disengage the two armies at Depsang and Demchok has been declared completed, while troop de-escalation and de-induction along the LAC still need to be agreed upon and will require verification on the ground and using satellite images. There is, however, no template of the agreement. Nor has the government given details of the new “patrolling arrangements” it has agreed to. Reports that the PLA has been granted access at Yangtse, the area on the Arunachal Pradesh boundary where it had attempted to transgress in 2022, have also not been explained by the government. Unfortunately, this lack of clarity is now part of a pattern….

If there is a larger purpose to restoring sustainable peace and tranquillity at the India-China border, then New Delhi must begin by restoring some transparency to its plans for the future of the ultra-sensitive sub-region at its northern peripheries.”

Jabin Jacob on what we still don’t know:

“With the benefit of some distance from the events of 2020, Indians should also now be asking more questions.

Why did China do what it did? What might it do next? Why has Indian expertise been lacking in answering these questions? Or, if the expertise is available, why has it not found greater acknowledgement and public visibility? Equally important are questions of accountability surrounding the events of 2020 itself. What were the lapses on the Indian side that caused intelligence on the Chinese build-up to be ignored? Why has public accountability not been forthcoming? Without answers to these questions and more, India will remain unprepared for the next border crisis with China.”

10 Links

Supriya Sharma on India’s ‘forgotten war’.

“For decades, large swathes of southern Chhattisgarh, also known as the Bastar region, have been a stronghold of Maoist guerillas who say they are fighting to protect the local Adivasi population from the depredations of a capitalist state. The jungle war has been a death trap for the security forces.

In 2010, the Maoists had ambushed and killed an entire unit of 76 personnel in the forests of Dantewada in a matter of hours – the largest single-day loss Indian security forces had ever suffered in any war, internal or external.

Fourteen years later, the security forces have struck back. The October 4 operation caps a year-long campaign in which Chhattisgarh police claim to have killed 189 Maoists in Bastar – the highest-ever annual tally notched up by the security forces.

But the simple binary of security forces versus Maoists hides a crucial difference.”

John Reed and Sylvia Pfeifer on “the battle to build India’s military jet engines.”

Ayush Tiwari on how Adityanath’s police raj is backfiring on the BJP in Uttar Pradesh.

“The alleged plot to kill Khalistan propagandist and lawyer Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, for which prosecutors in the United States have indicted Delhi businessman Nikhil ‘Nick’ Gupta and former Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW) officer Vikash Yadav, had all the comic elements of an old-fashioned Bollywood cop movie.

For India’s external intelligence service, this case is arguably the biggest debacle in its history. It raises hard questions about whether R&AW is truly prepared to stage operations under the gaze of hostile agencies overseas. Even setting aside diplomatic embarrassment, the allegations suggest breathtaking lapses in communication security, amateurish handling of sources, and poor tradecraft.”

Sourav Ray Barman on Kanhaiya Kumar ‘ruffling feathers’ in the Congress.

A longread from Shivani Kava and Anisha Seth on the Kannadiga vs outsider divide in Bengaluru.

Also, on China, from former Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale:

Suhas Palshikar on how in Maharashtra, the big fight is “over nothing.”

Vineet Thakur and Ladhu Ram Choudhary on how a Nazi occupied India’s first chair in IR.

Harish Damodaran on the paradox of stagnant rural wages.

Can’t Make This Up

Earlier this year Rubio introduced a Bill calling on the US to effectively treat India as an ally.

Gabbard was also a co-chair of the ‘India Caucus’, and has received support from Hindu Nationalists in the US.