'Tripolar' world, wage stagnation in India, cheap e-buses and more links

Plus, another grandiose GDP prediction.

On the Political Cycle,

, and I spoke about Russia’s efforts to influence democratic societies in the West, and why the US sometimes gets similar accusations in India. Listen and subscribe:

10 Links

(in each case, emphasis added).

The government seems to have suddenly woken up to the fact that wages have been stagnating in India, affecting the country’s demand and consumption story:

“What has triggered conversations within corporate boardrooms, key economic ministries, and between the two, is a report prepared for the government by industry chamber FICCI and Quess Corp Ltd, a tech-enabled staffing firm with 3,000-plus clients, which showed that the compounded annual wage growth rate across six sectors between 2019 and 2023 ranged between 0.8 per cent for the engineering, manufacturing, process and infrastructure (EMPI) companies and 5.4 per cent for fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) firms…

Chief Economic Advisor V Anantha Nageswaran referred to the FICCI-Quess report in at least a couple of his addresses in corporate gatherings, and suggested India Inc needs to look within, and probably do something about it.”

Of course, if they had paying attention this wouldn’t be news. Here is a careful examination from Maitreesh Ghatak, Mrinalini Jha and Jitendra Singh, from January 2024:

“The story that emerges by looking at some of the key statistics relating to the labour market in India is: from 2017-18 onwards the LFPR has shown an increasing trend and the UR a declining trend. While this appears like a positive development, looking at the numbers more closely, we see signs that are indicative of a deteriorating quality of employment generation.

The main driver behind the trend in the aggregate indicators of the labour market is the rise in employment in the self-employed category, which, in turn, has been driven by a rise in unpaid family work subcategory…

In contrast, those holding the 'good jobs' – the regular wage and salary earners – have seen a decline in the share of total employment in the economy between 2017–18 and 2021–22. There has also not been any real increase in their earnings.”

On a side note – the surprise pick for Reserve Bank of India Governor is now prompting many to expect a rate cut as soon as February.

Saheb Singh Chadha has a detailed analysis of how the India-China relationship has evolved since the Galwan clashes in 2020. Echoing Chadha’s conclusions, Harsh Pant and Vivek Mishra propose that “India’s burgeoning defense and security partnership with the US, which has increasingly impacted the security, stability, and balance of power in the Indo-Pacific region, could have been a leading reason for the incursion.” Shanshan Mei and Dennis Blasko also read India-China relations through this lens:

“China has probed both India’s and America’s reaction to its activities in a sensitive area out of the media spotlight, attracting only minimal foreign attention. It likely gathered important intelligence about the scope and depth of U.S.-Indian military cooperation — such as bilateral military exercises in the region and intelligence sharing — as well as insights into the Indian military’s tactics and vulnerabilities in the region. Furthermore, the People’s Liberation Army has tested its ability to sustain large forces in an extreme environment while enhancing its strategic depth and dual-use infrastructure near the Line of Actual Control.”

Ashok Kantha still has questions about what exactly was agreed between India and China:

“The Minister has underlined that the Indian side “would not countenance any attempts to change the status quo unilaterally”. However, has not the status quo along the borders been changed by China since April 2020? In the absence of facts being shared in the public domain, we can only speculate. This writer’s discussions with retired senior military officials who have served in Eastern Ladakh suggest that there is denial of access to several traditional patrolling points under new arrangements…

The Chief of Army Staff has reiterated even after the announcement of the understanding on disengagement in Depsang and Demchok on October 21 that “we want to go back to status quo of April 2020”. However, the Ministry of External Affairs no longer refers to the restoration of the status quo ante. If we acquiesce in facts on the ground changed to the advantage of China, this will be another example of a successful deployment of the Chinese playbook of grey zone operations which involves making incremental gains while staying under the threshold of an outright military conflict.”

Manjari Chatteree Miller, meanwhile, suggests that US ought to consider what a ‘tripolar world’ – with India as the third pole – might mean:

“The United States hardly considers the possibility that India might pose a challenge of its own. Instead, American officials have reached out to India as a partner and encouraged its rise, hoping New Delhi will amass enough power to counterbalance Beijing. They seem to want India to become a regional power, perhaps even something akin to a “third pole” in the global order.

American officials should consider a more complex strategy. New Delhi is a valuable partner in many domains, including the competition with Beijing. But India is notoriously intransigent in world politics. Its behavior on the global stage sometimes worries even those countries that want or need to develop friendly relations with it. Should India acquire the heft to become, as U.S. officials hope, a true counterbalance to China, it will likely also consider itself a counterbalance to the United States. In short, a tripolar world, with India as the third pole, will not strengthen Washington’s or Beijing’s hand. Instead, it will produce a more unstable global dynamic.”

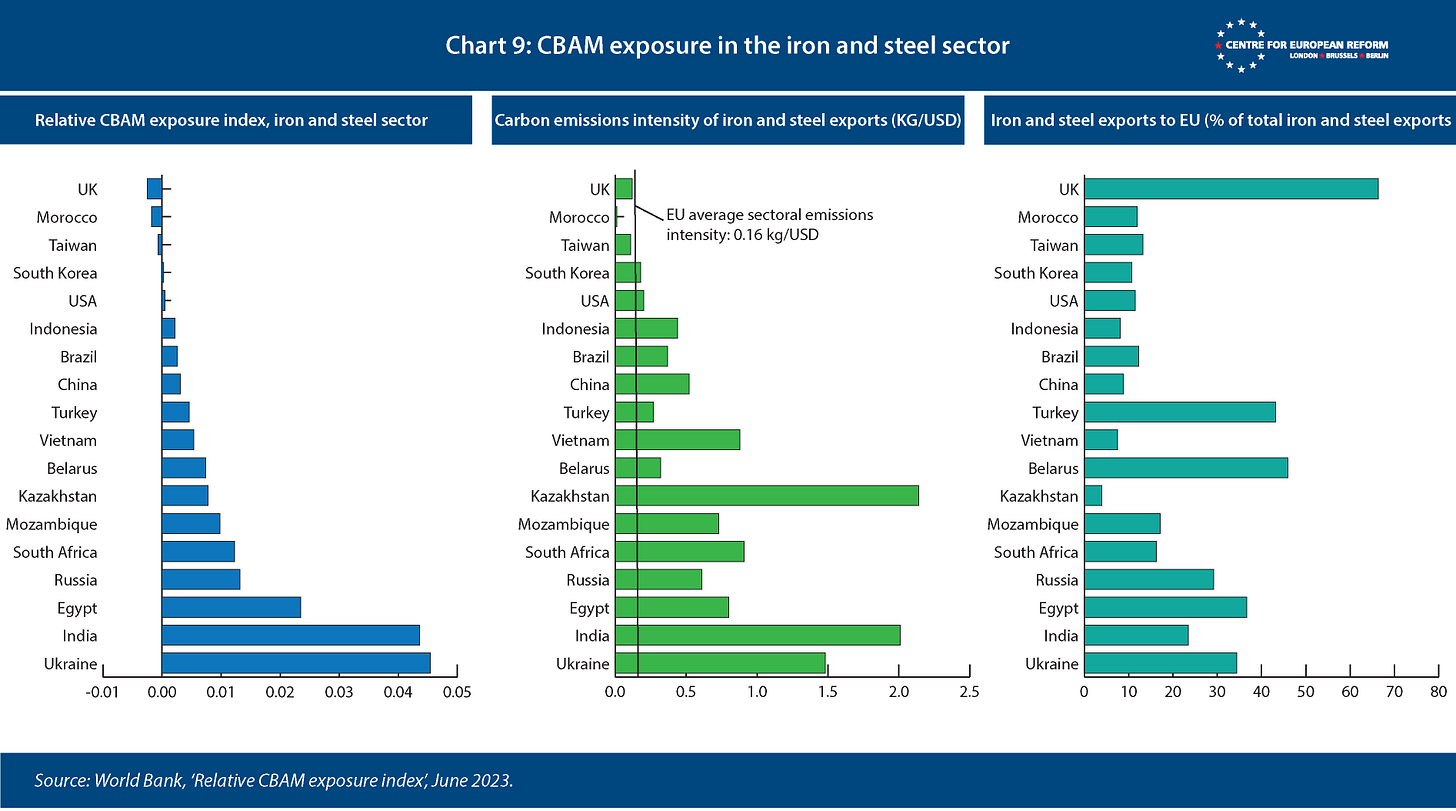

Elisabetta Cornego and Aslak Berg offer learnings from the transitional phase of the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, which India has decried as an ‘arbitrary trade barrier’:

“India is uniquely exposed to CBAM, both due to the volume of its exports to Europe, their carbon intensity and the fact that it does not yet apply a carbon price domestically…

With respect to the rest of the world, there is a good chance that China, India or other countries like South Africa or Brazil will mount a WTO challenge to CBAM… But beyond the legal risk, there is also a political risk that CBAM, regardless of its merits as a climate mechanism, is perceived as primarily a protectionist tool…

If China and OECD economies may be able to withstand the coming CBAM shock, other large emerging economies – such as India, Vietnam, Brazil, Ukraine and Türkiye – will be affected by CBAM and may need additional EU support in adapting their industry to a net zero future.”

Lou Del Bello reports on an interesting effort that helped Indian cities get access to e-buses on the cheap (while also effectively contracting out public transport):

“In 2021, Acharya found a way to achieve that heft. She banded together five major cities for two giant acquisitions of buses. CESL called it the Grand Challenge, an act of financial alchemy that would ultimately put 12,000 on the road for little upfront cost. Instead of buying buses, New Delhi, Kolkata and the other cities would bid out to private companies the opportunity to run the entire bus service over 12 years.

Each city would specify the size of the fleet it was seeking. And each manufacturer—including Tata Motors Ltd., India’s largest bus maker—assembled a consortium of operators to provide the drivers, e-buses, battery replacements, charging stations and maintenance. The groups would compete for a contract that specified a per-kilometer price. Each contract was so big (48.7 million rupees per bus over the dozen years) that it was worth a look, even for Tata.

The municipalities ended up paying just shy of 49 rupees per kilometer, 27% less than the cost of operating with compressed natural gas without the need for subsidies. Acharya’s pay-as-you-go model helped spur cities to commission 29,000 e-buses, up from fewer than 500 four years ago.”

Puja Changoiwala tells the story of The Mooknayak, a news organisation with a focus on issues related to the Dalit community:

“Over the past few years, The Mooknayak has received several Indian and international journalism awards for its reportage, including a Best Media Organization award at the Human Rights and Religious Freedom Journalism Awards in 2022; however, the outlet's journey has hardly been easy. Kotwal says that she has been subjected to constant online abuse — and the smear campaign, she adds, has led to a significant drop in the money the platform raises through public donations, its main source of funds. In the past few months, Kotwal has had to downsize her editorial team from 20 to six, and now, she is afraid not just for her daughter, but also the future of The Mooknayak.

“I do not know how long we can go on this way,” she says.

Maktoob media carries prison notes, written more than a year ago, by Sharjeel Imam. Meanwhile, Betwa Sharma writes on Umar Khalid’s fourth appeal for bail, four years and three months after being arrested:

“Khalid’s bail has been rejected thrice even though the Supreme Court has repeatedly said that bail is the rule and jail is the exception, and a division bench of Justices Abhay S Oka and Augustine George Masih reiterated that dictum in August 2024 in cases where there were grave allegations of terrorism and money laundering.

Our study of the chargesheet, witness statements, and the prosecution’s arguments suggests that the larger conspiracy case was mounted to discredit the protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019, which picked up in December 2019, and selectively punish some of the protesters for standing up to the government…

Our reporting shows that the allegations against Khalid are based on inferences, conjectures, and fabrications.”

Aditya Mani Jha writes about authors on Pratilipi, an online self-publishing portal that has, among other things, helped “turn small-town housewives into authors with a mass following”:

Take Vaishali Manthalkar for example. This 36-year-old housewife living in Solapur district, Maharashtra, began writing stories on the app in 2019. “I had always loved reading stories,” Manthalkar said during a telephonic interview. “Around six-seven years ago, I was in a phase where I was reading a lot in Marathi. And one day I felt like I too could write a ‘paarivaarik’ story.”

The ‘paarivarik’ (family-centric) bit would become a signature for Manthalkar who now has over 60,000 followers on Pratilipi. Her serialised Marathi story ‘Reshmi Naate’ regularly clocks lakhs of views with every new instalment. The narrative begins with the story of a ‘contract marriage’—a practice deployed in Maharashtra usually by young women seeking to get visas. But it soon settles down into the familiar rhythms of the good ol’ soap opera—fathers and sons, mother-in-law and daughters-in-law chafing against each other’s likes and dislikes...

It is heartening to see early-career practitioners like Jadhav and Manthalkar earning upwards of Rs 1 lakh per month via their fanbases. For both housewives, this is the most money they’ve ever made. Indeed, Jadhav who lives in a village near Pune confirmed that for the 18 years of her marriage she had never even considered working for a living outside her in-laws’ house.”