Welcome back to India Inside Out, a newsletter on Indian politics, foreign policy, history and more. This is the monthly link round-up, pointing to stories we haven’t had a chance to touch upon on the newsletter, insightful commentary and some other cultural tidbits from me.

A reminder: I’ll be in Philadelphia, at U. Penn’s Center for the Advanced Study of India, over the next two months and am aiming to make trips out to New York and Washington, DC. If you’re around at all and would like to meet, get in touch!

Before we get to the links a couple of plugs:

The Election Tricycle

This week on the podcast I co-host with Emily Tamkin and Tom Hamilton, where we track elections in India, the US and the UK (subscribe to the show on Apple, Spotify, elsewhere!), I break down what the Indian election actually looks like, why it’s so long – 44 days this time – and how different it is from the British and American systems.

Do listen, subscribe and share:

Starting this week, you can also get access to a premium version of the podcast – with listener questions, potted profiles and fun vignettes from our elections. Sign up now on Hubwave.

Decolonising Indian IR

On India in Transition, a publication from the Center for the Advanced Study of India at the University of Pennsylvania, we have an interesting piece from Kira Huju, examining debates that have been bubbling away in academia for a little while now. Who gets to ‘decolonise’ the academy? What does it mean when Hindutva nativism is wedded to decolonial theory?

From Kira Huju’s piece:

“I call these actors “postcolonial populists.” They express themselves differently from Narendra Modi’s India to Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Turkey, but the basic grammar is historical narratives of victimization at the hands of the West are employed to dress up contemporary authoritarian politics as a project of decolonial liberation. The “non-Western Self” is presented as an uncontaminated and romanticized subaltern who must be liberated from Western impositions like secularism or liberal democracy.

In India, “decolonial Hindutva” marries the nativist politics of Hindutva with the formerly left-wing language of anti-imperialism. It invokes historical repertoires of resistance against the British Raj to sell the project of revanchist nationalism against imagined enemies—from “Westernized” dissident academics and journalists at home to “imperialist” human rights monitors abroad. All foreign critique is dismissed as an imperial incursion into the sovereign affairs of Bharat; all domestic critique attests to the insufficient decolonization of the Indian mind. Indian colonial subjugation is dated not to the arrival of the British East India Company in the mid-18th century, but the advent of the Mughal courts in the 16th century, allowing Hindutva historiography to subsume anti-Muslim politics under the banner of decolonial nation building.”

Go read the whole piece.

And if you would like to pitch to India in Transition, where we carry pieces on contemporary India from across disciplines, check out the submission guidelines here, and get in touch with me.

Links

I’ll be coming back to the story of Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal’s arrest in an upcoming edition, but there’s been plenty of commentary on it already. Read Pratap Bhanu Mehta on how the mask of democracy has come off and why Kejriwal was an important target for the BJP, Suhas Palshikar on one more step towards an ‘Opposition-less India’, Neerja Chowdhury on whether this represents overreach from the BJP or a decisive political move and Sugata Srinivasaraju on the Aam Aadmi Party’s past.

Electoral Bond details continue to tumble out. The Wire collects seven issues that deserve further investigation, offering a useful summary of some of the major revelations. ‘Project Electoral Bond’, a collaborative project bringing together three news organisations – Newslaundry, Scroll and The News Minute – and independent journalists, continues to carry out vital work in drawing the links between political funding and policy decisions, including banks, telecom companies, pharmaceutical firms and more.

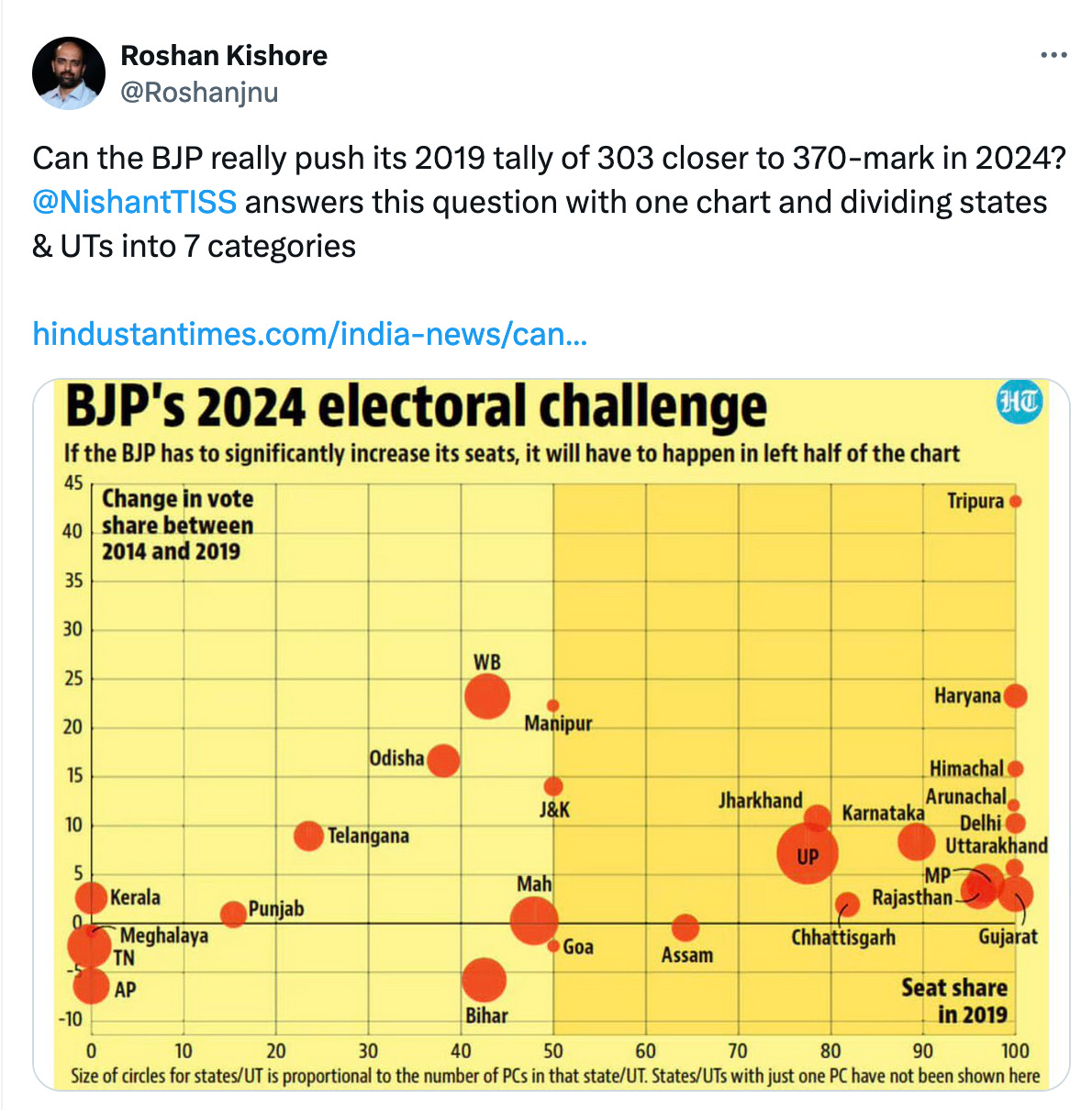

The Electoral Bond disclosures might tell us plenty about policymaking and the way that political funding operates in India. Yet they’re unlikely to hurt the BJP, argues Shoaib Daniyal. Roshan Kishore goes a bit further, making the argument that, while transparency in political funding is important, it is “politics, not thugs or suitcases of cash, [that] drives the essence of the contest.” On a somewhat related note, Ankita Barthwal and Francesca Refsum Jensenius write about the resilience of partisanship in Indian politics.

Yamini Aiyar wrote in the Economist about the damage done to Indian democracy under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in the same week that she also announced her departure from the Centre for Policy Research.

Here’s Milan Vaishnav on what has happened with CPR:

”At a time when India occupies a unique geopolitical sweet spot, its ability to fully exploit this opportunity rests on three mundane, but essential, endeavours: Building robust institutional capacity, developing farsighted policy, and enhancing the country’s human capital stock. All three pursuits are imperilled when the values of academic freedom, independent thinking, and critical analysis are curtailed. In this respect, CPR’s story serves as an important cautionary tale…

One would have to be wilfully naïve to believe that vitiating a research organisation will bring the gears of policymaking to a halt or raise enough eyebrows to force a self-assured government to change tack. After all, there are elections to be fought, economic deals to be struck, and foreign relations to be negotiated. Policy conversations in the nation’s Capital will go on without missing a beat. But one would have to be equally naïve not to grasp that this onward grind proceeds with attendant costs — of a discourse that is diminished, a talent pool that is enfeebled, and a spirit of independent inquiry that is sapped. To paraphrase an old line from Eleanor Roosevelt, small minds discuss people and average minds discuss events. It is great minds that discuss ideas.”

Arzan Tarapore has a report on the policy options available to India and other non-belligerent states if they would seek to deter a Chinese attack on Taiwan, without getting directly into the fray.

Shekhar Gupta argues that Narendra Modi and Amit Shah are campaigning, not for 2024, but 2029. “If you take a closer look at the BJP’s flurry of alliance-making, a long-term pattern is clear. Today, the BJP is carefully choosing allies already in decline, with a poor negotiating position, whose decline can then be hastened as it moves into their space.” This is something I also wrote about last week, albeit from a different angle. Meanwhile, Asim Ali looks at the BJP’s hesitancy in foregrounding a pro-incumbency campaign, instead preferring a campaign seeking “a mandate characteristic of an aspiring political hegemon.”

It’s worth looking closely at India’s more recent trade deals, particularly the just-concluded one with the European Free Trade Association, both in terms of details but also how they are being sold in a world where – the conventional wisdom goes – the ‘free trade’ era seems to have been a mistake. John Reed writes about India’s quid pro quo strategy and Gulshan Sachdeva explains how the EFTA deal indicates the potential for larger deals with Europe.

Flotsam & Jetsam

A beautiful piece on Sri Lankan author Shehan Karunatilaka’s oeuvre.

A review of AR Venkatachalapathy’s latest, on VOC and the Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company.

A Lebanese choir sings Kehna Hi Kya.

Sundeep Dougal curated this incredible Holi playlist.

Plus, three quick book recommendations based on what I’ve been reading most recently:

Ornit Shani’s How India Became Democratic (2017) – which tells the story of how universal franchise actually came to be in India, post-Independence – might be familiar to those who study political science, but returning to it ahead of the 2024 elections offers a really fascinating reminder of the incredible experiment that is Indian democracy.

The gorgeous Mad Sisters of Esi, by Tashan Mehta, whose first book I also absolutely loved. It’s hard to offer any sort of synopsis for Mad Sisters, but if you’re happy to immerse yourself in a fantasy world that runs on joy, melancholy and emotional bonds and isn’t too bogged down by rule-making (even if the rules are there), go read this!

The first thing Tejaswini Apte-Rahm’s The Secret of More did to me was make me feel guilty. Apte-Rahm’s debut novel is based on research into the life of her great-grandfather, who “began life in Bombay in a chawl, sharing a room with 3 other men. But when he died in 1952, it was in his magnificent sea-facing mansion, having made his fortune in the textile, silent film and sugar industries.” The book seeks to utterly immerse you into that world, offering a fictionalised account of a character whose life broadly followed her great-grandather’s trajectory, and in doing so documenting minutely what everything looked, sounded and tasted like, giving us as the author writes, a sort of “origin story” of Bombay. Anyone who has thought about looking into their family history with hopes of turning some of that material into narrative (but then put it off for later) is going to feel deeply envious.

Can’t Make This Up

In Ramanthapuram, it’s OPS vs OPS vs OPS vs OPS vs OPS.