Plugs

This Republic Day also marked the 11th anniversary of Scroll.in, the award-winning independent digital news organisation where I spent my formative journalism years. Read this note from editor Naresh Fernandes, and go support Scroll.in’s incredible work.

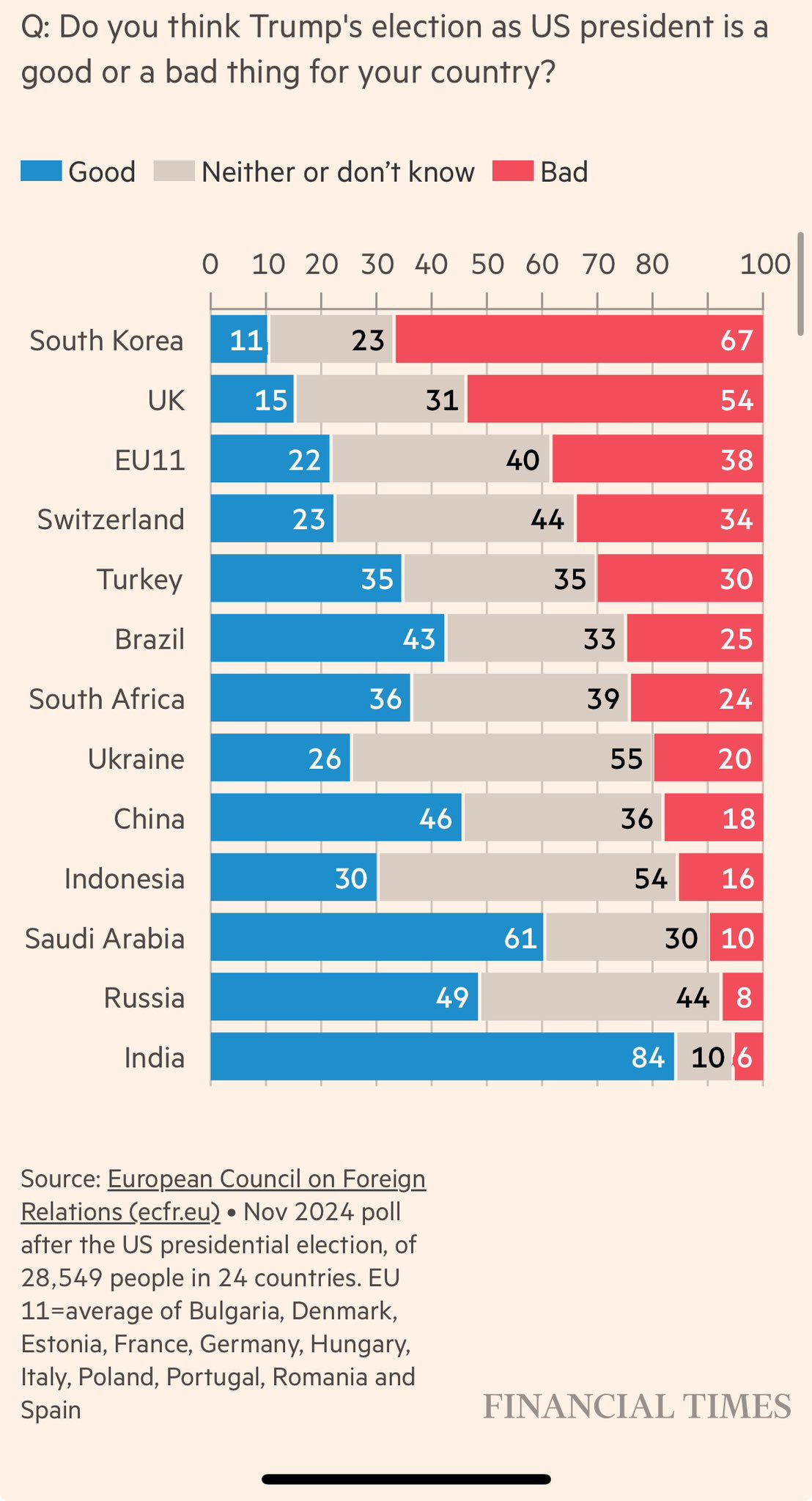

On The Political Cycle, we spoke about how Donald Trump re-taking the reins of the US is being seen on the outside, and in particular about this Financial Times chart, based on an ECFR poll.

Listen to this week’s episode:

And check out episodes from the last few weeks on modern oligarchy and the politics of disasters and climate change.

For the Center for the Advanced Study of India’s India in Transition, I spoke to political scientist Eswaran Sridharan on coalitional politics in India and what we learned from 2024.

“E. Sridharan: What we are seeing is very early days yet. But nationally, you seem to be getting a broad center-right alliance centered on the BJP, which is, at the moment, strongly ideological and what I have called the “coalition of the disadvantaged,” with the Congress shifting leftwards compared to its traditional stand.”

We also carried pieces on the occupational safety questions surrounding semiconductor manufacturing in India, whether Galwan was an ‘intelligence failure’, and the idea of Bollywood stars as cultural diplomats.

If you’re interested in writing for India in Transition, where we carry short analytical pieces by scholars working on contemporary India, get in touch!

For South Asian Voices, I summed up India’s 2024, and what we might expect in the year ahead:

“Even without the Trump factor, there are myriad challenges that India faces over the coming year: continued ethnic conflict in Manipur, ongoing violence spurred by majoritarian politics, the massive risks engendered by climate change, and instability in Myanmar, Bangladesh, Pakistan and beyond.

But the major developments of 2024 – Modi’s reduced majority at the national level, urgent questions about the sustainability of India’s economic growth, and the volatility that a Trump administration will bring – all make the task of retaining a foothold on the much-touted sweet spot even harder in 2025. On the domestic policy front, how the BJP handles the tension between its reduced numbers and the major reforms it promised voters, like the Uniform Civil Code and One Nation, One Election, will be crucial. The first full Budget of Modi’s third term, expected in early February, should also offer an indication of how the government plans to address the unexpected growth shock towards the end of 2024. And with Bihar, India’s third-largest state by population, going to the polls in the latter half of 2025, there is likely to be no let up in heated political speech or competitive welfarism.”

Also read the rest of SAV’s 2024 in Review, looking across the region.

And finally, a plug for something that falls outside the usual ground covered on this newsletter: For Kallisto Club, a podcast for “daring parents and parents-to-be who refuse to choose between their dreams and their family”, I spoke about parenting across multiple cultures, my love for Alison Gopnik’s The Philosophical Baby, what the first few months are like and what lessons if any I managed to note down amid the sleep deprivation.

10 Links

Bilahari Kausikan, former Singaporean diplomat, on what Trump’s transactional foreign policy means in much of Asia:

“To many countries in Europe, the return of Donald Trump to the White House is seen as a momentous, almost apocalyptic, shift that is likely to disrupt alliances and upend economic relations. Meanwhile, American adversaries such as China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia anticipate that the incoming administration will mark an opportunity to advance their anti-Western agendas. Yet there is another region of the world, one that includes many U.S. allies, partners, and friends, that views Trump’s return more calmly.

Across a large part of Asia, from Japan and South Korea in the north, through Southeast Asia—the linchpin connecting the Indian and Pacific Oceans—to the Indian subcontinent in the south, a second Trump administration does not arouse the same strong emotions that it does among many in the West. For these countries, there is far less concern about Trump’s autocratic tendencies and contempt for liberal internationalist ideals. The region has long conducted relations with Washington on the basis of common interests rather than common values.”

Michael Ignatieff attempts to read Trump’s Canada and Greenland talk:

“If this is how to make America great again — hegemon over a bi-continental sphere of influence, with the US homeland as its heart — this might just be Trump’s quid pro quo for accepting Russian and Chinese spheres of influence and letting India tack between the two. Accepting their spheres of influence, provided they recognise his, would allow him to cut the Gordian knot that has tied America’s strategic interests to Europe and Asia.

He’s never had any patience with the Washington liberal elite’s vision of America providing global public goods in a rules-based liberal international order. If his strategic competitors accept an American sphere of influence in its own hemisphere, what strategic interest would America still have if China blockades, invades and absorbs Taiwan? If Russia imposes direct or indirect control over Ukraine, what would that matter to the US? If first eastern Europe, and then western Europe, becomes a satellite in a Russian sphere of influence, why should America try to stop it?”

Branko Milanovic on a shift in mainstream economic commentary:

“I do know that many mainstream neoliberal economists like to treat the appearance of Donald Trump as an Act of God. They treat him as an earthquake or some sudden storm whose origin nobody can fathom… I would like, on the contrary, to focus on the abandonment of neoliberal principles in the international arena… The goals are no longer free movement of goods because tariffs stop them; movement of technology is limited because of the so-called security concerns; movement of capital is reduced because the Chinese (and most recently Japanese as In the case of US Steel) are often not allowed to buy American companies; movement of labor has been severely curtailed. So what essential ingredients of neoliberal globalization have been left intact? …

The current abandonment of the principles of neoliberal globalization leaves the entire field of international development in chaos because it is not at all clear what types of policies should be suggested to, or imposed on, the rest of the world. One cannot imagine how a World Bank mission to Egypt could argue for reduced tariff rates or lower subsidies while at the same time the most important country, not only economically but in terms of suggested or enforced economic ideology, the United States, is raising its tariffs and subsidies. The entire ideology which underpins international economic relations has to be rethought.”

Kenneth Juster and Mark Linscott think Trump and Modi can make a deal:

“Ignore the conventional wisdom in Washington and New Delhi that the U.S.-India trade relationship is likely to deteriorate during U.S. President Donald Trump’s second term: The two countries in fact have a huge opportunity to expand trade and a realistic path forward for doing so.”

Yamini Aiyar on one of those big misconceptions about the Indian state:

“Contrary to popular wisdom, the Indian state is remarkably understaffed but in line with popular beliefs it is, at the lower end of the hierarchy, paid remarkably well. Given the significance of government jobs in our polity, an unusual democratic bargain has been struck: one that generates enough political pressure to keep wages – particularly at the lower end of the bureaucratic hierarchy where the bulk of the state is hired – high but accepts low staff and high vacancies as the trade-off. In public debates on the Indian state and its routine incompetence, these contradictions and capacity constraints have been ignored, to our own peril.

See also Aiyar’s analysis of the NITI Aayog at its 10-year anniversary.

Supriya Sharma on the forgotten Maoist war in Bastar:

“Last year saw an intensification of bloodshed in the region. Chhattisgarh police claimed to have killed 217 insurgents in 2024 – the highest number for any year since the counterinsurgency began. In December, Shah visited the state capital Raipur and triumphantly reiterated that the police were on course to ending the insurgency by March 2026.

Laying down deadlines in any conflict is a recipe for disaster. It leads to shortcuts and missteps, as Scroll’s reporting has shown. While in a few major operations, the security forces managed to target the Maoist leadership with great precision, several encounters have been marred by allegations of the security forces killing low-level cadres, or worse, unarmed civilians in cold blood and presenting them as reward-worthy Maoists. Scroll contributor Malini Subramaniam’s latest ground report on a botched-up encounter that left four children injured brings out the horror of what is unfolding…

The same week Mukesh Chandrakar was murdered for uncovering the truth about a road project, eight DRGs and their driver were killed when the security vehicle they were travelling in was blown up by the Maoists. The Adivasi policemen were returning from an operation in which five suspected Maoists, also Adivasi, were killed – “suspected” because only ground reporting can tell us who they actually were.

And this is the tragedy – the national media has almost entirely given up on reporting from the ground in Bastar. Most reports in major newspapers are largely based on the press statements of the police. It is as if the country no longer cares about the war in Bastar.

Brave local reporters, however, continue to do their work – as Chandrakar’s death shows, at a steep cost.”

Arzan Tarapore on the “long shadow of the Ladakh crisis.”

“The impact of the military build-up on both sides of the border remains unclear. It is an open question whether India is any better postured to deter Chinese aggression than it was in 2020, when it offered no meaningful deterrence…

The motivations for China’s 2020 incursions remain a mystery, but their effect has been clear: The seriousness of the threat prompted India to heavily reinforce its military presence on its northern border. This build-up came at the cost of Indian investments in military modernization, especially in force-projection capabilities in the Indian Ocean.”

Miscellany

Can’t Make This Up

Also, from this year’s Republic Day parade: