India Outside In #2: Why it is dangerous for India to believe the world is 'multipolar'

A conversation with Rajesh Rajagopalan, Professor of International Politics at JNU.

“I think the economics of the world, the politics of the world, and the demographic of the world is making the world more multipolar.”

“The world is moving towards greater multi-polarity through steady and continuous re-balancing.”

“The Indo-Pacific is at the heart of the multipolarity and rebalancing that characterizes contemporary changes.”

“The United States is moving towards greater realism both about itself and the world. It is adjusting to multipolarity and rebalancing and re-examining the balance between its domestic revival and commitments abroad.”

Those are all comments by Indian External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar over the last few years. Indeed, Jaishankar is a big votary of the concept of multipolarity – the idea that the world is not dominated by just one power (the US), or two (the US and China, just as it was the US and the USSR during the Cold War), but is instead now seeing a global order with a number of powers that are somewhat equally matched in terms of economic and military capacity and influence.

Jaishankar sometimes speaks of the need for establishing a multipolar world. And sometimes his comments seems to suggest the world is already multipolar or will soon be there.

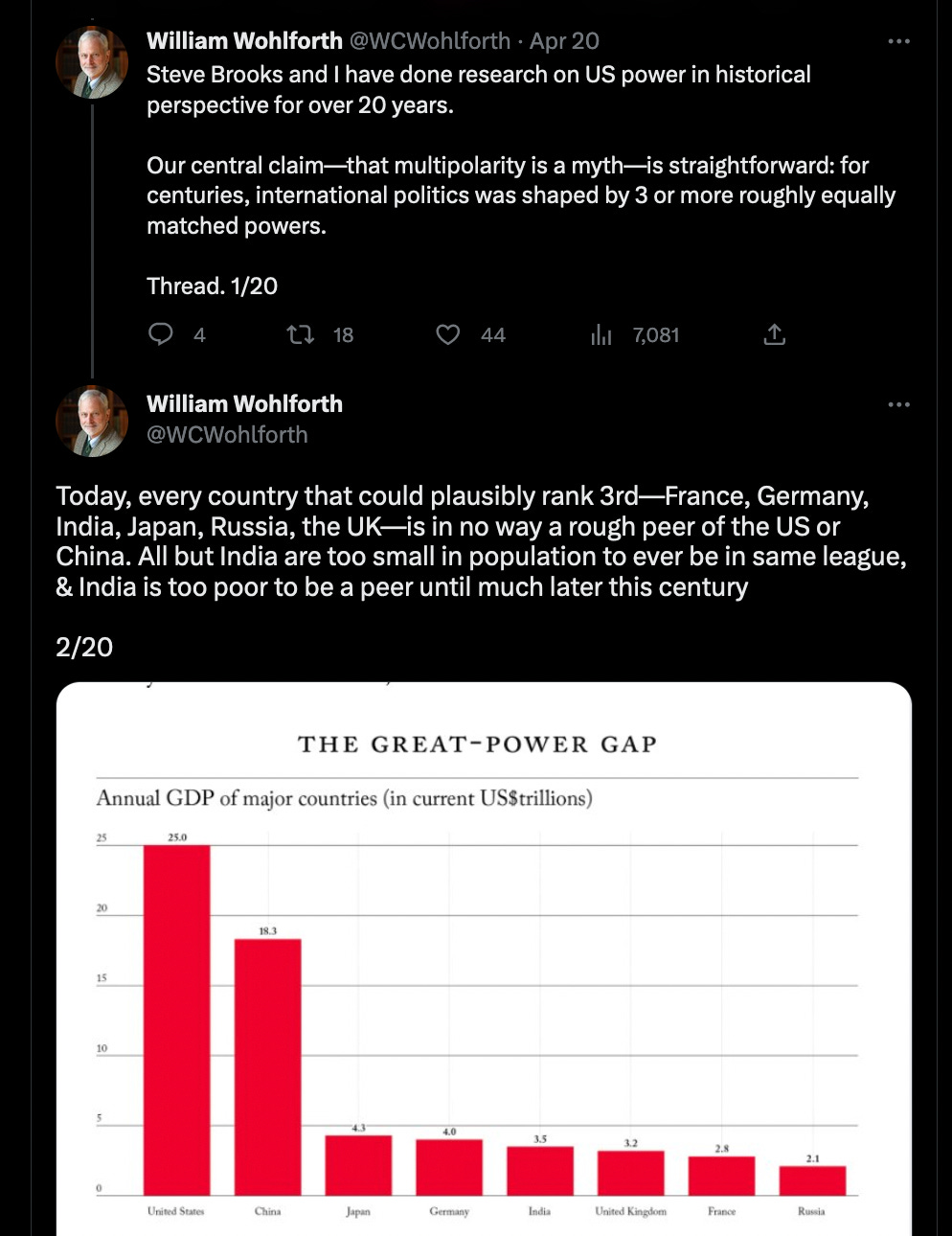

Not everyone agrees. Stephen G. Brooks and William C. Wohlforth, in a Foreign Affairs article in April 2023, argued that multipolarity is a ‘myth’.

Brooks and Wolworth argue instead for “partial unipolarity”, in part because Chinese military power remains “regional.”

Rajesh Rajagopalan, professor of International Politics at Jawaharlal Nehru University and author of Second Strike: Arguments about Nuclear War in South Asia thinks the answer is clearer: We are living in a bipolar age. And it is dangerous for India to think otherwise.

I spoke to Rajagopalan about multipolarity vs bipolarity, why he thinks that Jaishankar describing the world as multipolar is problematic even if it is a purely rhetorical tactic, and what he made of Ashley Tellis’ much discussed piece from earlier this month – with the controversial headline, ‘America’s Bad Bet on India’ – which argues that the US should not expect India to side with it in a military confrontation with China, unless its own security is directly threatened.

To start off, how do you read Jaishankar and India’s articulation of a multipolar world, either as an aspiration or as a reality?

I’ll start with the reality: Of course, it is not [a multipolar world].

There are different ways of defining polarity. Academics by and large look at it as either unipolar world or a transition to a bipolar word. Some argue that the world may be bipolar in the Indo-Pacific region because of China’s power there, but not bipolar in a global systemic sense. Since this is a peaceful period – not marked by war – it’s very hard to identify the boundary between unipolar and bipolar. But my sense as an analyst is that the world is already bipolar, because the way polarity is measured is purely in terms of material capacities, and on this, clearly China has the wealth and the intention.

Wealth by itself doesn’t fully define polarity, it has to be converted into things like military capacity. So Japan or Germany becoming closer to the US in terms of GDP levels would not constitute bipolarity. But in many ways, the US and China are closer to each other than anyone else. China’s GDP is now almost comparable to the US, or by some measures it is greater. Polarity is not an exact science – it doesn’t need to be exactly at the same level for bipolarity. If you look at the US-Soviet balance for example, at no point did the Soviet Union cross even the 50% threshold in comparison to the US economy. Nevertheless we called it bipolar.

China is already well past that stage. The other part of polarity is that there has to be sufficient distance between the polar powers and other great powers. And if you look at US-China and everyone else, the gap is huge. So it’s both the fact that US and China are comparable, and the huge gap between them and everyone else, that makes it a bipolar system. The only reason there is some doubt about whether it is unipolar or bipolar is because the US has a global [military] capacity, and that China still hasn’t developed that capacity.

But that measurement is also a problem because the Soviet Union never developed that global capacity in the way that the US did. As I see it, China in the Indo-Pacific, the Asia-Pacific, has that capability and is also projecting now – it’s building a large number of aircraft carriers, it has a military base in Africa – we can expect more of that to happen. It will reach beyond its region. Also, we don’t see any immediate possibility that this will change, that others will catch up, because the gap is already so huge. Somebody crossing that threshold is very difficult for the immediate future. So it is going to be bipolar for at least a decade.

If I had to throw in an outsider’s question: If these concepts are fuzzy even to academics, why is it important to identify what sort of polarity we have right now? What is the importance of the concept?

Most people use it in a descriptive manner. But the real importance comes from an IR theory perspective. Some IR theories project a theoretical utility to characterising polarity. They would argue that in a bipolar system, states behave in a different way than in a unipolar or multipolar system. There are consequences in terms of state behaviour and outcomes.

It’s only within a Realist school that these have a relevance. There has been a well-set theoretical argument that bipolar systems are stable, while multipolar and unipolar systems are unstable. Again, even Realists don’t all agree on that, but this is the general, dominant Realist view. The argument being that with only two major players in a bipolar system, they are better able to manage conflict. Whereas in multipolar systems, there are multiple great powers of roughly the same capacity, leading to greater insecurity, nobody knows who’s aligning with whom, whether your partners might betray you, all of that makes the system much more unstable, according to this theory.

Until the 1990s, Realists never bothered about unipolar systems. They didn’t think they were possible. The assumption was that there will always be some kind of balance, no power would be able to be so dominant as to have unipolarity. Even after 1991, for almost two decades, there was no theorising of unipolarity, because most Realists assumed that this was a passing phase. The first major theorising happened towards the end of the 2000s. After 20 years, they had to admit it and do some theorising.

It is the consequences that make it important to figure out which system you are in.

Bipolar systems are also very rare, we don’t have bipolar systems at all over long periods of history. The only real one that we had was the Cold War, which coincided with nuclear weapons, and I think those had a bigger role to play in that stability – the lack of war between the polar powers. But the general consensus is that bipolar systems are more stable. So there are consequences depending on what system we’re in.

Speaking of these consequences, you’ve actually argued that it is dangerous for India to approach the world as if it were multipolar when it’s not. Why do you believe that is?

If we think it’s a multipolar world, then we think that there are many other powers we can partner with. [But] in a bipolar system in which one of the polar systems is a neighbour, we have only the other polar power to partner with, the US. There is a practical, political consequence to saying it is multipolar and that there are multiple other powers we can partner with. If it’s a multipolar world, we don’t really have to partner with the US. We can partner with Japan, France, Germany, Europe, whoever we think the other powers are.

To some extent, we have been looking for these partnerships, not to give up on the US, but to reduce the centrality of the US. But if its a bipolar system, then it’s only the US, really speaking, who can provide us with the support that we need, because others are not capable enough. In that sense, if we think it’s multipolar and go around looking for all these partners, who we think are capable but aren’t actually, then in a crunch it could potentially become dangerous, and lead to minimising our partnership with the US. France, Germany and all are really not capable of helping India balance against China alone. If you think that they are, and that it’s a multipolar world, then we are in for a bit of shock.

Some have argued that the talk of multipolarity is more of a rhetorical tactic, rather than the way that the MEA actually sees the world. You’ve argued that even if it is rhetorical, we might be susceptible to believe our own story…

We have a tendency to believe our own rhetoric. Also, I see this narrative not just in the MEA. It’s much more widespread. I see it seeping into the system. As a deliberate narrative tactic, I can understand. But when it is spreading like this, not just within the MEA but outside, then it is dangerous.

There is another reason they are doing this. The assumption in the multipolar rhetoric is that we are one of the poles. I think that’s also very dangerous. A key element of Realism is that you have to know your strength, but also your weakness. You have to read the power balance well, and your behaviour has to reflect that. From Kautilya to Thucydides, one of the key things is, ‘trim your sails to the prevailing wind.’ If you think you are stronger than you actually are, that could set us up for a serious problem down the line. We can fool ourselves into thinking that we are much more capable than we actually are.

What would an India that acknowledges bipolarity look like? You’ve argued (in an analysis from 2017) that what we have with the US right now looks more “like a profit-driven bandwagoning relationship”, so what would be different if we accepted bipolarity? Would it mean further alignment with the US?

It’s not a question of aligning or allying, that gets into problems of what is an alliance and so on. Look at China and Pakistan. That’s probably one of the strongest alignments, even though there isn’t a mutual defence component to it. Given the political realities in India, an alliance is unlikely and may not even be necessary. But what we need is a much stronger security partnership. This would involve discussing contingencies, what we would expect of them, what they would expect of us, what kind of cooperation would happen etc…

If you look at the example of a war like Ukraine, what material support would be needed – that would be the kind of thing we would discuss. Even if you look at 1962, when [Jawaharlal] Nehru asked for US help, the kind of things that he was asking for – squadrons of US air support to protect Indian skies – that can’t be done overnight. Or even artillery or ammunition, they need to know what we need, you have to discuss these things prior to a contingency. So even if you are not fighting together, you still need to have support – everything from diplomatic support to material support – [and for that] there has to be prior planning and discussion. That is what I would mean by closer security cooperation.

It is not necessary that the multipolarity rhetoric takes away from security cooperation, we can have both. I don’t care if they want to talk about multipolarity, while strengthening security cooperation. But as of now I don’t see that. I see a decline or at least a break in the partnership with the US while we are doing all these other things. From the outside to me, that’s what it looks like.

I have no problems with all these other strategic partnerships and everything we’re doing with others, but [I want to see] greater security partnerships with the US, Quad and other partners, so that if there is a need, we have [already] discussed what needs to be done. If the situation ever arises, then we have some prior planning – including contingencies like Taiwan, South China Sea and so on – so that all expectations from each other are discussed prior to something happening. As of now my understanding is that that has not happened. That’s what I see as a real problem. I don’t really care what they call it – bipolar, multipolar – if they do this. But for now I see all these calls for multipolarity as diminishing this other part, and that’s what I find worrying.

You did an interesting job laying out these options for India in your Carnegie paper, written before the Ukraine war and before the 2020 Ladakh clash. For the reader – what would India be risking by articulating bipolarity and taking a bipolar approach? Would it mean having to take sides on something like Taiwan? Would there be a short-term danger of facing more hostility from China?

I’m not really sure we need to articulate it clearly. As I said, I don’t really care what the articulation is, [I care] more about what we’re actually doing. For public consumption and to ensure we don’t antagonise China, we can keep talking about multipolarity. I don’t have a problem with the talking part of it, I have a problem with the doing part. The level of cooperation, involving discussing contingencies – obviously the US does that with alliance partners like Japan, but the AUKUS agreement for example, explicitly talks about them discussing what can be done.

Now, we don’t even have to go down the path of a treaty. As long as we have that kind of cooperation, that suffices. We can keep talking about multipolarity, we can keep doing BRICS and SCO, but that should not come at the cost of doing these other necessary things with our partners, the US, Japan, France and so on.

Do you think the historical baggage and the military dependence on Russia, means there is fear within the Indian establishment about broadening the security partnership with the US? Or is that irrelevant now because of Sino-Russian cooperation?

I think there is a little bit of concern about that, but the primary driver comes from domestic ideological reasons. Some of this I can understand. We are a post-colonial society. The West’s colonial history makes part of this understandable. But we need to get over that. In 1971, we did that very well. Brushed off a copy of an agreement, quickly made the Russians sign it, forced them to support us and as soon as the war was over, we dumped the Russians. It’s actually a good example. But the reason why that won’t work is that we were then dealing with a much weaker country – Pakistan – and we needed the Russians onboard to give us some cover vis a vis China, which was also fairly weak at the time, and primarily in the UN Security Council.

That is no longer a viable strategy vis a vis China, which is much much more powerful. We need much more careful planning, not an ad-hoc measure. The dependence we have on Russian arms is a real concern. But even more than those concerns, I think there is a deeper ideological discomfort about partnering in a formal sense with the US. And I think that’s a much bigger problem.

To recap for the reader, were India to accept a bipolar world, your argument is that India cannot take the nonalignment path as it did in the previous bipolar system – the Cold War – because China is right on our doorstep. You believe India would have to more clearly pick a position.

In the last bipolar order, the two powers were far from us. So we could play them off against each other, which is what we did, and which is what a number of developing countries did. And that is what a number of developing countries may do today, if you go to Africa, the Middle East, maybe even Latin America, definitely Europe. Those countries being far away from the two polar powers can afford to play one off against the other and get the best from both sides.

We got enormous economic support during the Cold War. In fact, we were the largest recipients of American economic assistance and we got an enormous amount of diplomatic and military assistance from the Soviets. We even had security guarantees from the US throughout the 60s, vis a vis China, and also nuclear guarantees after China tested its nuclear weapons.

Because they were far from us, we could play one off against the other. We are no longer in that position. Now, we are in a dispute with one of those polar powers, and they are in our neighbourhood. India, as well as South-East Asia and North-East Asia do not have the luxury of playing one off against the other. I know ASEAN is doing that, but I think ultimately ASEAN cannot really afford to do this. Power doesn’t travel well over distance. The further away you are, the less somebody’s power affects you. But we are right on their borders.

You engage with the counter-intuitive option also in that paper – India accepting Chinese hegemony – though you rule it out. Because that is also an option in a bipolar world. Is there a scenarion in which you see India-China detente?

It’s not entirely unlikely. For example, look at domestic American politics. If [former US President Donald] Trump were to come back and decides to pull out the US from its commitments to the Indo-Pacific, NATO and so on – because there is a growing domestic opinion in the US that this is not our fight – then we are left in a situation where we may not have very many choices. In which case, we have to be pragmatic and make our peace with the Chinese. It may not be a peace that we like, but we’ll have to do what we can to survive that period. We won’t have a choice at that point, because nobody else can balance against China. This is a short-term possibility.

The longer-term possibility is that the US steadily declines, and over 20-30 years China becomes a global hegemon. Again in that context, we would end up in a situation like Latin America today – which is that they can complain all they want, but they are under American hegemony, they can’t balance against it.

There was a piece I wrote a few years ago called the ‘Latin Americanisation of Asia’ saying if the US were to decline over the long-term – this would take many years given how powerful it is today – but if it were to happen, it might withdraw from the Indo-Pacific not because of intent but capacity. Again, then India would have to consider some way of living with China. Under the current circumstances, when we do have a choice of balancing, of course we should balance.

In a recent piece about lessons for India from the Ukraine war, you wrote: “though this is an impressive balancing act, it also runs the risk of India becoming overconfident in its indispensability and underestimating the need for friends in a potential future crisis. In other words, India’s success, so far, could be teaching it the wrong lesson about the current global security order.” Tell us more about this lesson.

The US, given its power, can afford to be more forgiving of its partners. Whether it is France, during the Cold War period, or Germany, Turkey or Israel – all of these are countries that have done things that the US had disagreed with, but it has been able to ignore because it can afford to do that. In India’s case, Ashley Tellis’ piece indicates concerns [from DC]. Just because the US is being solicitous to India doesn’t necessarily mean that they need India more than India needs them. That’s a big concern, because there’s a constant refrain here that somehow India is necessary for the US and India is indispensable.

Let’s assume for the sake of argument that India and the US were not partners. India would still have to balance against China. India has no choice. So if the US were not partners with India, it would still get the benefit of India balancing against China. We can’t make peace with China, just because we’re not partnering with the US. But the US will get the benefit of our balancing against China, ‘for free’ so to speak. What they want is for India to balance against China, which they will get in any case. The [Indo-US] partnership is to help strengthen India, so that it provides a better balance against China than it can on its own, which would help the US.

But push comes to shove, it’s not necessary for the US to partner with India. And the US already has other military partners like Japan and Australia, whereas India doesn’t really have anyone else that can help balance against China. Our value to the US is being partly exaggerated, because the US is very forgiving and good at doing alliance management, not standing on ceremony, not taking offence at various things and so on. But we tend to think that their solicitousness is because of our indispensability. That is a fear I have.

I wrote that piece a couple of months ago, and it just got published. But, Tellis’ piece to me suggests that there is a growing concern in DC. Tellis has been one of India’s long-term boosters, for 20 years he has been campaigning for closer relations between India and the US and has always been positive about the relationship, but that piece got a lot of negative comments and opposition from Indian observers. Nevertheless it is a piece that partly indicates that concern that India is overplaying its hand and assumes it can do whatever it wants.

We’re running out of time, so our final three questions. What are you broadly working on now?

I have a long-term book project looking at Indian foreign policy from a Realist lens.

Two other things: One is looking at Realism from a regional perspective. One of the unfortunate things about Realism being so dominated by American scholars is that they tend to focus on great power politics. And Realism as it operates in the global system and Realism as it operates in the regional arena has significant differences.

[The other] is about Kautilya. I think he is more appropriate as a Realist, because he was writing at a time when the empire was not an empire, it was one kingdom amongst many, and so it is more appropriate to our situation where we have a number of powers who are tussling. It’s not really Great Power Realism. Great Power Realism is useful, but it’s not particularly helpful from an Indian perspective, because we’re not a Great Power, and we have to exist within a regional system where a lot of other complications arise.

If I’m not incorrect you mention some of this in a chapter in the Routledge Handbook on International Relations of South Asia. What misconceptions about India’s foreign policy do you find yourself having to correct all the time?

One is about non-alignment. There was an ideational component to non-alignment. But there is [also] a proper Realist explanation for non-alignment. You can explain it on the basis of power realities that India faced. India was a fairly secure state in the Cold War period in the sense that China was not much stronger than it, and within the region it was the dominant power. It really did not have much of a security concern or a significant security concern, which allowed it to adopt non-alignment.

There is an explanation for non-alignment from a purely material Realist lens, whereas I find almost all works on non-alignment tend to see it as ideational or ideological. To the extent that some do see it in a Realist sense, they see it as a Realist strategy, as opposed to an explanation for it from a Realist side. Those are different things. That’s one major misconception, that I hope to address, whenever I get to finish my book. Unfortunately non-alignment has been defended as Realism, but not explained as non-alignment.

Three books or pieces that have influenced you?

Kenneth Waltz’s Theory of International Politics. The first time I read it, it was like a window opening, the world suddenly started making sense. There are a lot of problems with Waltz. I first read Waltz four or five decades ago, and over the years I have recognised a huge number of problems with his conceptions, but nevertheless for me it is still the primary international relations theory text.

Balance of Power in World History, edited by Stuart J Kaufman, Richard Little and William C Wohlforth. This book hasn’t received the attention it should have. The assumption of a lot of Realism is that balance of power always recurs. They demonstrate that balances of power do not always happen, which is why throughout history you don’t always have balances but hegemonies, empires and so on.

Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security by Barry Buzan and Ole Waever. This made me think more of regions, and influenced me in moving away from the global system.

On the subject of Indo-US ties, read also:

Ashley Tellis expands on his piece, in a conversation with James M Lindsay of the Council on Foreign Relations.

Ashok Malik’s response to Ashley Tellis’ piece arguing that the Taiwan conflict is not the right lens with which to view Indo-US relations.

Pranay Kotasthane on the ‘two equilibria’ in this relationship.

That’s it for this edition of India Inside Out. Send feedback, funny memes and great links to rohan.venkat@gmail.com