India Inside Out Links: The Adani meltdown, Modi's bashful minority outreach and more

Plus, 'can't make this up'.

Last week was a busy one for India watchers.

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman unveiled the government’s last full budget ahead of the 2024 elections, with a big focus on government-funded capital expenditure paid for by squeezing the subsidy bill. Former Congress President Rahul Gandhi concluded his 150-day-long Bharat Jodo Yatra. India and the US announced a high-level initiative on defence and emerging technologies, including military jet engines and semiconductors. New Delhi also announced an ambitious plan to cooperate in defence, energy and tech in a trilateral format with France and the UAE.

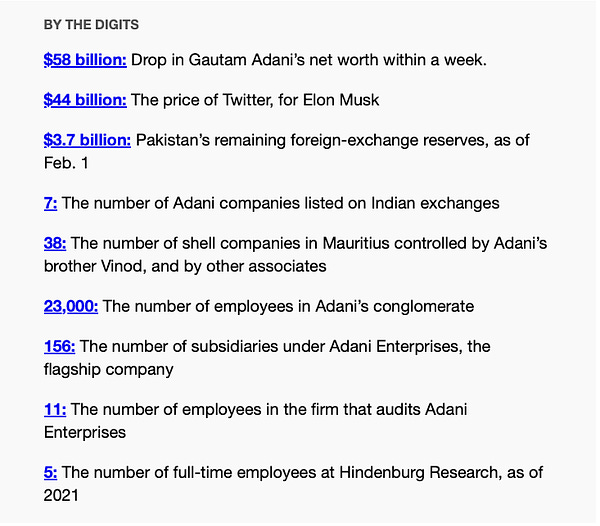

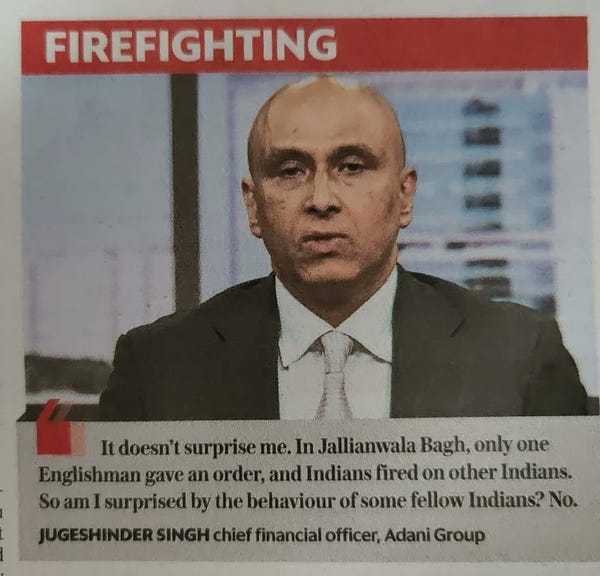

And the Adani Group – a conglomerate with close ties to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government that has grown massively since 2014 – saw its market value drop by more than $100 billion after a short-selling research firm alleged stock manipulation and accounting fraud, prompting the group to abandon a $2.5 billion stock offering and many others to ask what this meant for India’s economic story.

Here is some of what I was reading this week.

Adani Meltdown: Bloomberg has a tick-tock on what actually happened in the hours after the short-seller’s report saw Adani stocks go into freefall, forcing the group to cancel its record share sale. With domestic and foreign observers calling this a test for India’s market and regulators, Mihir Sharma argues that what really worries Indians is not the chance that Adani’s stocks are juiced up, but that the group – which has effectively been picked as a national champion – won’t be able to deliver on everything it has signed up to do:

“If Adani’s companies can deliver a fraction of what he has pledged, then perhaps, in time, they might even grow into the valuations they have already achieved on paper. If they fail, then a lot more goes down than his investors; Adani will take down India’s industrial policy with him. Their big bet on him will then rebound on India’s banks, on India’s politicians, and on India’s citizens.”

See also: This piece by Adam Tooze on the Adani fracas, Aswath Damodaran on what it means for Indian markets and Suhasini Haidar on worries in India’s neighbourhood, where the group has taken up major infrastructure and energy projects, in some cases allegedly at the Indian government’s behest.

The Budget: For most, the big takeaway from the 2022-23 Budget was that the government did not make more populist choices in terms of increased spending, despite this being the last full budget ahead of the 2024 election. (It is important to remember, however, that Modi’s PM-Kisan income support for farmers scheme came in the interim budget in 2019, right before the elections). Instead, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has chosen to increase capital expenditure by a third (up 150% over the last three years), and to pay for that by dramatically reducing the amount spent on subsidies/welfare, such as India’s rural employment scheme.

This suggests that, in the absence of spending and investment from the private sector (presumably because of a lack of demand in the economy), the government still feels the need to drive growth itself – but is making a bet that it won’t need to provide a big safety net for its citizens despite global uncertainty. As Rajeswari Sengupta writes:

“The government clearly feels compelled to do the heavy lifting of investing and boosting demand in the economy because the private sector is not investing in capacity expansion. This is deeply concerning because for an emerging economy like India to grow at 5-6 per cent, and more importantly, to create the jobs required to absorb the millions of young people entering into the labour force every year, it is imperative that the private sector starts investing on a large scale.”

Read also: AK Bhattacharya on the risky calculations, Rathin Roy on the macro-fiscal concern, Sajjad Chinoy on the budget’s ‘artful balance’ and Jayati Ghosh on the social spending cuts.

The Great Indian Poverty Game (IYKYK):

BJP’s (clandestine) outreach to minorities: Earlier in January, following the Bharatiya Janata Party’s national executive meet, the media revealed that Prime Minister Narendra Modi had told the party’s leaders to reach out to Muslims, to organise ‘Sufi nights’ and visit churches. Then suddenly the BJP’s media team tried desperately to reach journalists and tell them not to publicise this information.

DK Singh explains why:

“Why deploy media managers to try to ensure that the people don’t know about it? Because he sincerely believes that the party’s core anti-Muslim votebank may not like it…

The BJP probably don’t want any confusion in the minds of their core support base by showing a bleeding heart for minorities.”

See also: Nistula Hebbar on the BJP’s plans to expand in South India.

Rahul Gandhi’s Bharat Jodo Yatra: What did the former Congress President achieve with his 150-day cross-country walk ostensibly aimed at uniting the nation and spreading an ‘apolitical’ message of peace between communities? Scroll.in’s Arunabh Saikia traveled to 14 districts in India’s ‘Hindi heartland’ through which Gandhi had walked to find that the yatra went a long way towards building (or resurrecting) the Congress leader’s image – but without denting Modi’s. And now that it’s done, all the internal Congress factionalism that was put to the side to make way for Rahul Gandhi will now be back in focus.

See also: Sanjay Srivastava on the Yatra and Rasheed Kidwai on what comes next.Citizen vs ‘Labharthi’ (beneficiary): The welfare policies of the Modi government (or ‘new welfarism’, as Arvind Subramanian put it) have been key to its sustained popularity in the face of poor economic outcomes. In this Seminar essay, Yamini Aiyar argues that the BJP’s distinct welfare model can be identified by how it characterises the people receiving benefits:

“Students of India’s welfare state have routinely characterized the Indian welfare state in the framework of patron-client relationships. These frameworks are invoked to understand the dynamics of rent-extraction, identity based patronage and clientelism as explanations for the historic failures of the Indian state to deliver welfare goods to all citizens.

I would argue that none of these effectively describes the BJPs welfare model and the shift it under-pins from the citizen to the ‘labharthi’. This is welfare based on loyalty, benevolence and above all the persona of the party leadership. It is best described as ‘patrimonial welfarism’.”

The BBC documentary:

More censorship: Vasudev Devadasan on a government proposal (for which consultation has now been pushed forward) that would require social networks to take down links to any pieces that a government mouthpiece has declared ‘fake news’, even though it has repeatedly been wrong in the past:

“Imagine that a citizen’s social media post about the poor condition of a national highway goes viral. The PIB or maybe even the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways declares the post is “fake” and notifies internet platforms, resulting in the post’s removal. Granting government bodies the authority to remove “fake” content in this manner raises serious constitutional concerns as it restricts free speech beyond what is constitutionally permitted and bypasses the safeguards against government censorship set out in Section 69A of the IT Act.”

India-Russia ties: C Raja Mohan on how New Delhi’s dependence on Moscow for defence supplies constrains its foreign policy options and why India needs to get out of its ‘long infatuation’ with Russia:

“In the past, the Jan Sangh – the precursor of the BJP – was among the consistent critics of Delhi’s tilt towards Moscow. Today it is in power. While it has little ideological empathy for Moscow it is trying to manage the difficult inheritance of military dependence on Russia. But sections of the Hindu right share the visceral anti-western attitudes on the left of the Indian political spectrum; and some sections of the right appear to admire Putin’s muscular policies and would like to see India emulate them.

Together much of the political class, the retired ambassadors and generals, and the commentariat appear ready to buy into many outrageous Russian justifications for its invasion of its neighbour and its claim that Ukraine has no right to exist…

The Indian foreign policy elite was shocked by the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. It might be in for a similar experience in the coming years as Putin and Russia come out very diminished from the failing war in Ukraine.

Official Delhi will have to eventually deal with a world of declining Russian influence.”

See also: Sameer Lalwani and Happymon Jacob on whether India will ditch Russia.

Bonus: A Pratinav Anil piece – which not everyone is going to agree with – arguing that Mohandas Gandhi has not aged well.

Flotsam & jetsam

Can’t Make This Up

Thanks for reading India Inside Out. If you have feedback, links to share or ‘Can’t Make This Up’ suggestions, put them in the comments or email me at rohan.venkat@gmail.com